If you read only one article today, read this one. It’s powerful and poignant. The article was written by Forrest Wilder and appears in the Texas Monthly, a terrific publication.

To understand why Republican legislators from rural districts helped to defeat vouchers in Texas, read this article about the schools of Fort Davis in Jeff Davis County in rural West Texas. The superintendent is a bedrock conservative who is dead set against vouchers. His schools are on the verge of bankruptcy due to the state’s Byzantine school-finance system. The state government doesn’t care. At the end, you will understand Governor Abbott’s long-term goal: to eliminate property taxes and completely privatize education.

Texas doesn’t have a mile-high city, but Fort Davis comes close at 4,892 feet. The tiny unincorporated town is nestled in the foothills of the Davis Mountains, where bears and mountain lions and elk stalk among pine-forested sky islands. Fort Davis is the seat of Jeff Davis County, whose population of 1,900 is spread among 2,265 square miles, 50 percent bigger than Rhode Island. The sparsely populated desert country of Mongolia has nearly seven times the population density of Jeff Davis County. Odessa, the nearest city to Fort Davis, is two and a half hours away. The state Capitol is six and a half.

For Graydon Hicks III, the far-flunged-ness of Fort Davis is part of its appeal. He likes the high and lonesome feel of his hometown—the “prettiest in Texas,” he says. But these days, it has never felt further from the state’s political center of gravity.

For years, Hicks, the superintendent of Fort Davis ISD, has been watching, helplessly, as a slow-motion disaster has unfolded, the result of a flawed and resource-starved public-school finance system. Over the last decade, funding for his little district, which serves just 184 K–12 students, has sagged even as costs, driven by inflation and ever-increasing state mandates, have soared. The math is stark. His austere budget has hovered around $3.1 million a year for the past six years. But the state’s notoriously complex school finance system only allows him to bring in about $2.5 million a year through property taxes.

Hicks has hacked away at all but the most essential elements of his budget. More than three-quarters of Fort Davis’s costs come in the form of payroll, and the starting salary for teachers is the state minimum, just $33,660 a year. There are no signing bonuses or stipends for additional teacher certifications. Fort Davis has no art teacher. No cafeteria. No librarian. No bus routes. The track team doesn’t have a track to train on.

But Hicks can’t cut his way out of this financial crisis. This school year, Fort Davis ISD has a $622,000 funding gap. To make up the difference, Hicks is tapping into savings. Doug Karr, a Lubbock school-finance consultant who reviewed the district’s finances, said Fort Davis ISD was “wore down to the nub and the nub’s all gone. And that pretty much describes small school districts.”

“I am squeezing every nickel and dime out of every budget item,” Hicks said. “I don’t have excess of anything.” When I joked that it sounded like he was holding things together with duct tape and baling wire, he didn’t laugh. He said: “I literally have baling wire holding some fences up, holding some doors up.”

The district’s crisis comes at a time when the state is flush with an unprecedented $33 billion budget surplus. Hicks is a self-described conservative, but he thinks the far right is trying to destroy public education. For years, the state has starved public schools of funding: Texas ranks forty-second in per-pupil spending. And yet Governor Greg Abbott is spending enormous political capital on promoting a school voucher plan, which would divert taxpayer funds to private schools. Public education, Abbott has repeatedly said, will remain “fully funded,” though public-education spending is lower now than when he took office in 2015, and the Legislature recently passed a $321.3 billion budget with no pay raise for teachers and very little new funding for schools. Unable to get his voucher plan through the regular legislative session, Abbott is threatening to call lawmakers back to Austin until he gets his way.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, long a champion of vouchers, is backing legislation that would attempt to appease rural Republican legislators—a bloc long wary of vouchers—by offering $10,000 to districts that lose students to private schools. Hicks can barely contain his anger when he hears such talk. He has been lobbying state leaders for years to fix the crippling financial shortages that plague districts like his. “Take your assurances and shove ’em up your ass,” he says, before softening a bit. “I’m so tired. I’m so frustrated. We have tried. I have fought and fought and fought.”

With each passing month, his rural district inches closer to financial ruin. If nothing changes by next summer or fall, Fort Davis will have depleted its savings. He doesn’t know the exact day that his school district will go broke, but he can see it coming.

It’s easy enough to grasp the basic problem in Fort Davis. But what’s going on beneath the surface is another story.

During my twenty years of reporting on Texas politics, I’ve often heard that only a handful of people in the state understand the school-finance system, with its complicated formulas, allotments, maximum compressed tax rates, guaranteed yields, and “golden pennies.” A former colleague of mine, who once spent months trying to make sense of the topic, warned me against writing about it. Karr, the school finance consultant, compares the process of making sense of our public education funding to encountering a fire at a roadside cotton gin on some lonely West Texas highway. “You drive off into that smoke and you might never drive out,” he said. “You might end up getting killed.”

A thorough explanation of the system is the stuff of graduate theses, but the broad strokes are straightforward enough. How a school district is funded begins with two key questions: How much money is the district eligible for? And who pays for it?

Here it’s helpful to use a venerable school finance analogy: buckets of water. The size of a school district’s bucket—how much money it’s entitled to—is largely determined by the number of students in attendance. Every district receives at least $6,160 per pupil, an amount known as the basic allotment, an arbitrary number dreamed up by the Legislature and changed according to lawmakers’ whims.

At this point in the article, Wilder goes into the intricacies of school finance in Texas. Very few people understand it. All you need to know is that some districts are lavishly funded while others, like Fort Davis, are barely scraping by and may go bankrupt.

Hicks is not alone in thinking the opaqueness is intentional. “They make it just as complicated as they can,” he said of state officials. “Because how do you explain something so complicated to the average voter?” In other words, if constituents can’t easily grasp the perplexing and unnecessarily knotty framework, it’s tougher to hold officials accountable for budget decisions.

Though the spreadsheets may be head-spinning, they tell a story. In a state where some wealthy suburban communities build $80 million high school football stadiums, Fort Davis ISD is one of many rural communities literally struggling to keep the lights on.

I first heard from Hicks in March 2021, when he emailed state officials and journalists with a dire message: “What, exactly, does the state expect us to do? What more can we do? What more do our children need to be deprived of? At what point does our community break?” Hicks has received few answers, even as his situation has grown more desperate.

When I visited him in April, we met in his office, where he keeps a book on Texas gun laws, a photo of his West Point 1986 graduating class (which included Donald Trump’s secretary of state Mike Pompeo), and a list of quotes from General George Patton (“Genius comes from the ability to pay attention to the smallest details”). Hicks, who’s stout and serious and talks in a sort of shout-twang because of partial hearing loss, wore a cross decorated in the colors of the American flag. He was eager to show me the fine line he walks between fiscal prudence and dilapidation. The first lesson came as he stood from his desk and I noticed the holstered handgun on his hip. The district, he explained, can’t afford to hire a school security officer, so he and eleven other district employees carry firearms.

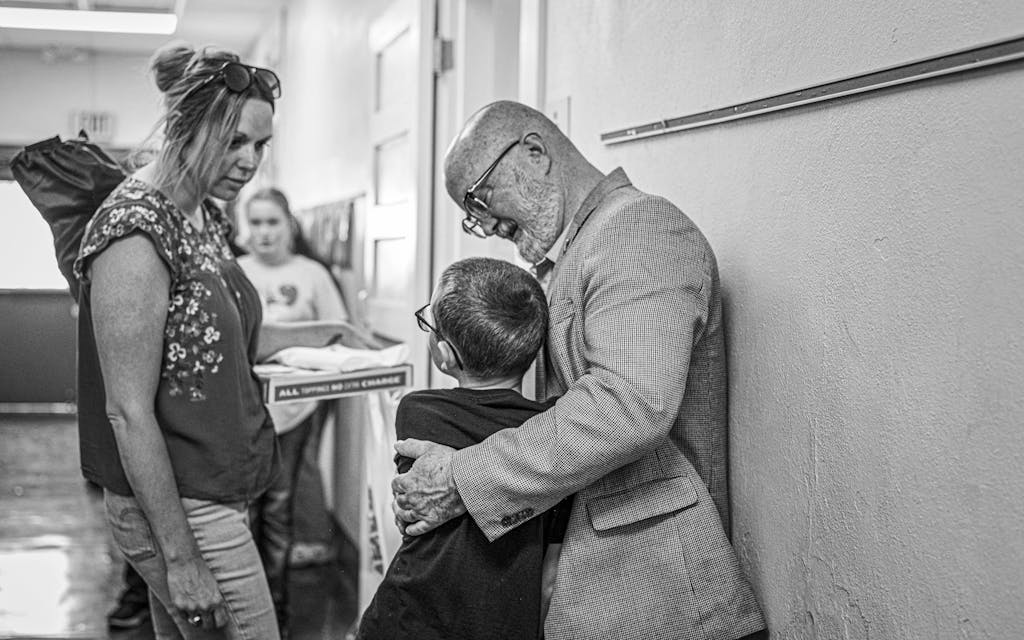

His family has been in the area since the 1870s, when federal soldiers still pursued Comanche and Apache from the town’s namesake garrison. His great uncle was one of the first superintendents of Fort Davis ISD. (At one point, Hicks showed me a copy of his great-uncle’s 1942 master’s thesis, “The Early Ranch Schools of the Fort Davis Area.”) Later, as we were walking around campus, Hicks’s ten-year-old grandson, a thin fourth-grader wearing blue-rimmed glasses and blue jeans tucked into a pair of cowboy boots, ran up to Hicks and gave him a hug.

Both the elementary school and the high school—where Hicks graduated in 1982—were built in 1929, Hicks explained. Walking through their timeworn hallways is to step back in time. In places, the plaster is flaking off the original adobe walls. The elementary school gym floor is bubbling up because of a leak under the foundation. The wooden seats in the high school auditorium have never been replaced. The urinals in the elementary school are original too. The newest instructional facility, a science lab, was built in 1973. In the summer, Hicks mows the football field, the same one he played on five decades ago. “Every bit helps,” he said.

The funding challenges create all manner of ripple effects. Hicks has trouble recruiting and retaining teachers, and some students drift away from school without extracurriculars to hold their interest. “You lose teachers, then you start losing kids, and then your funding gets worse,” he said. “It’s a circle-the-drain kinda thing. And it’s really speeding up for Fort Davis.”

The first problem is the size of the district’s bucket. For the last decade, TEA has calculated that Fort Davis’s Tier I annual allotment is between $2 million and $2.5 million, well short of its already spartan $3.1 million budget.

And then there’s the matter of how that bucket is filled. In the 2011–2012 school year, the state covered two-thirds of Fort Davis’ entitlement, about $2.1 million. Today, it chips in about $150,000, a 93 percent decrease. How to explain that change?…

In June 2019, the Big Three figures in state government—Abbott, Patrick, and then–House Speaker Dennis Bonnen—gathered at an elementary school in Austin for an almost giddy bill-signing ceremony. As a bipartisan group of lawmakers watched, Abbott signed into law House Bill 3, an $11.6 billion package of property tax cuts and education funding that had received near-unanimous support in both the House and Senate, a rarity in the highly polarized Legislature. “This one law does more to advance education in the state of Texas than any law that I have seen in my adult lifetime,” said Abbott.

For almost a year, an appointed commission of experts had met to discuss how to overhaul the school-finance system, issuing a report in December 2018 that called on the Lege to “redesign the entirety of our state’s funding system to reflect the needs of the 21st century.” HB 3 was the by-product of that prompt. Lawmakers rejiggered many of the system’s outdated formulas, offered pay raises to teachers, fixed some of the most glaring inequities, and reduced the amount of money recaptured by the state from property-wealthy districts. Most important, HB 3 represented a much-needed infusion of cash for struggling schools. The basic allotment was raised from $5,140 to $6,120 per student.

But HB 3 also exacerbated disparities among property-wealthy and property-poor districts. Because of changes to the way Tier II enrichment funding works, some communities were able to cut tax rates and generate significant new revenues from their tax base. For others, a minority of districts, HB 3 actually created new problems. Around 10 percent of districts saw a decrease in formula funding. This year, Alpine has $220,000 less than it would have had under the old system, even as some of the richest districts in the state—tiny West Texas communities with lots of oil wealth—saw their funding explode. Rinehart contrasts Alpine, which has almost no mineral wealth, with Rankin ISD, 130 miles northeast in the Permian Basin oil patch. While Alpine’s funding went down 2 percent, Rankin’s went up 339 percent. Even though Rankin is projected to return close to $100 million in recapture payments to the state this year, the district is fabulously wealthy. “Alpine’s budget is $10 million,” Rinehart points out. “Rankin’s is $14 million. We educate a thousand kids and they educate three hundred kids. So they are a third of our size and have a budget 40 percent larger than ours.”

Rinehart doesn’t begrudge Rankin’s wealth—she recently served as assistant superintendent there—but uses the Alpine–Rankin comparison as a “wild” example of how HB 3 exacerbated inequities, making the rich richer and the poor poorer.

Hicks, too, has noticed. “Rankin just built a whole new school,” he told me. “They got a new fieldhouse, a new gym. Two new science labs. A turf practice field, a turf game field. A new track, a new stadium. And my buildings were built in 1929.” Rankin is planning to build ten new “teacherages”—district-funded housing for teachers, important to attracting and retaining talent in areas with scant or affordable residences.

Jeff Davis County, on the other hand, has no oil and gas and very little industry; any school debt would thus be borne by homeowners through bonds. Hicks’s district has never issued a bond, in part because it would be unlikely to pass; the voters wouldn’t support a tax increase. The school’s ag barn was built in 2019 with local donations. The band program, suspended for nine years as a cost-saving measure, was only revived in 2023 after a philanthropist left his estate to the school.

To be sure, Alpine and Fort Davis are outliers. Most districts saw an immediate boost to their finances from HB 3, and advocates celebrated a meaningful investment in public education after $5.4 billion in devastating cuts in 2013. But even for those districts, the sugar rush from HB 3 didn’t last long. According to Chandra Villanueva, the director of policy and advocacy at the progressive nonprofit Every Texan, the $1,000 increase in the basic allotment was “roughly enough to cover one year of inflation….”

The property tax system and the school finance system are inextricably linked, Rube Goldberg–style. Twist a dial here and a light will come on over there. Slip a gear here and spring a leak there. As state lawmakers have prioritized tax cuts over public education funding, the trade-offs have grown clearer. This year represents a potential turning point. But rather than trying to solve the problem using the $33 billion budget surplus—a generational bonanza—Abbott and Patrick have overwhelmingly focused their attention on property tax cuts and a school-voucher plan loathed by almost everyone in public education, in part because it would threaten to strip even more funding from school districts.

The just-completed regular session was a bloodbath. The 88th Legislature began in January with the governor and lieutenant governor promising to pass a transformative voucher program and a record-setting $17 billion in property-tax cuts. Funding for public education, often a banner issue, was scarcely discussed. Even the House, the friendlier chamber toward public education, only proposed raising the basic allotment by $140, from $6,160 to $6,300 per student—far less than the $1,500 increase needed to keep up with inflation since 2019, according to the Texas American Federation of Teachers. But in the end, teachers and public schools got virtually nothing.

Teachers and administrators were stunned. Zeph Capo, the president of Texas AFT, called it a “joke.” HD Chambers, the executive director of the Texas School Alliance, accused Patrick and Abbott of playing a “hostage game” with Texas’s teachers and public school students by tying education funding to vouchers. “It’s pretty simple. The governor and Senate says, ‘If you don’t give us the kind of vouchers we want, we’re not giving you any money.’” The House refused to budge, and the regular session concluded without a deal on property tax relief, vouchers, and other GOP priorities.

Now, the governor has promised to convene multiple special sessions to take up the unresolved issues. The first special session began three hours after the regular one ended, and effectively wrapped up less than 24 hours later, with the House rejecting the Senate property-tax plan, passing its own program consisting solely of property-tax compression, and then abruptly adjourning. Abbott threw his support behind the House plan. The message to the Senate was clear: take it or leave it. If the Senate yields, the House version would push some school districts down to as low as $0.60 per $100, with no new source of revenue to backfill for the reduced funding in case of a bad economy.

Abbott has said his goal is to completely eliminate the main school property tax. In such a scenario, Texas’s thousand-plus school districts would be at the mercy of the Legislature for funding—a troubling scenario, says Villanueva. She suspects vouchers would then become inevitable. “At that point, it’s like, ‘You know what, we don’t have the money to fund schools. Everyone take five thousand bucks, figure it out for yourselves.’”

That day, if it ever comes, may still be far off. But the education system is in crisis right now, and unlike previous hard times, the state is flush with cash. The pain, Chambers says, is being intentionally inflicted by Abbott and Patrick. “Because of this one pet project that the governor has”—vouchers—“they are purposely creating a financial environment where every school district in Texas is being set up to fail.”

The result is that Texas schools, already operating on “shoestring budgets,” will have a harder time attracting and retaining educators, said Josh Sanderson, the deputy executive director of the Equity Center, a nonprofit that represents six hundred Texas school districts. They will run up deficits. They may have to cut extracurriculars and athletic programs. Some, like Fort Davis, may become insolvent and be forced to consolidate with another district, an often painful process.

As we were sitting in his red pickup with the engine idling outside his office, Hicks told me that he’d given up on lobbying the Legislature. He mentioned again that Patrick and other GOP lawmakers are trying to destroy public education by using vouchers to privatize schools, and he said that most other politicians “don’t give a shit about West Texas.” But for the time being he was still fighting: writing op-eds, firing off plaintive missives, asking concerned citizens to contact their legislators.

Toward the end of our visit, I asked Hicks what’s going to happen to his schools. “I don’t know,” he said. “I’m not patient enough to spend time with assholes in Austin, and I’m not rich enough to buy any votes.” TEA has suggested consolidating with another district—most likely nearby Valentine ISD—but Hicks said this would harm both Fort Davis and the other district.

He seemed resigned to his role as a Cassandra warning of impending doom, destined to be ignored. He reminded me that his grandson goes to school here, and that the painful road ahead feels both personal and existential. “If you don’t have a school,” he said, “you don’t have a community.”

Two months later, Hicks called me with some news. He’d decided to resign this summer, joining the mass exodus of school leaders that have fled the profession in the past few years. To anyone who closely follows public education in Texas, his reasoning was tragically familiar: He said he was too tired to fight anymore.