Can you tell the difference between truth and lies? How do you know what is true and what is false? Politicians have always boasted about their successes, but how can you tell whether they are exaggerating? That’s the job of fact-checkers, and not many newspapers have them on staff.

Glenn Kessler is a professional fact-checker. That was his job at The Washington Post for many years, where he applied the same rigorous standards to all politicians and elected officials, regardless of party.

He was recently invited to delivered the keynote address at the 2025 #SweFactCheck conference in Stockholm, hosted by the FOJO Media Institute at Linnaeus University.

Kessler posted his speech on his Substack blog. I think it’s a very important piece about our age of disinformation.

Good morning. For nearly fifteen years, I ran The Fact Checker column at The Washington Post. That gave me a front-row seat to the extraordinary rise — and more recently, the uneasy retreat — of fact-checking around the world.

When I began in 2011, political fact-checking felt like a growth industry. At first, there were only a handful of dedicated organizations; a few years later, there were more than four hundred, spanning over a hundred countries — across Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Many operate where press freedom is fragile. As a member of the advisory board of the International Fact-Checking Network, I helped draft the IFCN’s code of principles — a commitment to check all sides fairly and remain transparent about funding and methodology.

Many of you might have observed the expansion of that movement. You know the energy that drove it: the belief that shining light on falsehoods could raise the cost of lying and strengthen the public square.

During the pandemic, for instance, IFCN members created the Coronavirus Facts Alliance, pooling more than 12,000 fact checks in 40 languages. It allowed researchers to trace how identical myths — from miracle cures to lab conspiracies — jumped continents within days.

I should note that fact-checking is not about scoring points or humiliating politicians. It’s about equipping citizens to make informed choices — to look under the hood before buying what a politician is selling.

But growth in fact-checking has not meant victory over lies. The more fact-checking expanded, the more sophisticated the falsehoods became. It is an arms race between truth and lies, and so far, truth is losing ground.

When several hundred people gathered in Rio de Janeiro earlier this year for the annual IFCN conference, the atmosphere was tense. After a decade of expansion, fact-checking was under fire. Funding was drying up. The political headwinds were stronger. And even as we grew in numbers, so did the wave of misinformation swamping the world.

Consider what has happened in just the past year.

Meta, which after 2016 invested more than $100 million to fund a hundred fact-checking organizations, ended its partnership with U.S. outlets, though it appears Meta will still support non-U.S. fact-checkers through 2026. Google announced it would phase out its ClaimReview program — a system I helped foster — that gave verified fact checks prominence in search results.

The Trump administration dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, eliminating grants that supported emerging fact-checkers in Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America, and Asia.

In the United States, there is no federal government regulation of social platforms. But even nascent regulatory efforts in Europe may falter. The European Union’s Digital Services Act was designed to hold platforms accountable for misinformation. Yet European fact-checkers worry that enforcement could be weakened during trade talks with the current U.S. administration, which opposes such regulation.

Fact checking has even become a dirty word, an epithet scorned by opponents. There have been efforts to rebrand it, though I’m not sure a name change will mean much. The purveyors of falsehoods will still attack anyone who tries to correct the record.

There are many reasons for this global shift, but two stand out.

First, social media allows falsehoods to travel faster than truth can catch up. By the time a claim is debunked, millions may have seen the original post — and few will ever see the correction. We witnessed this during the war between Israel and Hamas, fought both on the ground and across digital networks, where competing narratives raced ahead of verification.

Second, more politicians now feel emboldened to lie with impunity. Autocrats always did, but now elected leaders in democracies deploy the same tactics to energize supporters and delegitimize opponents.

When I started to helm “The Fact Checker,” I focused on statements by politicians and interest groups — claims about jobs, health care, or taxes. But over time I found myself tracing a meme that originated on a fringe website and was recycled into mainstream discourse.

Take the false story that athletes were “dropping dead” from COVID vaccines. It began on obscure Austrian sites linked to a far-right party, written by anonymous authors who did not exist. Those posts were amplified by U.S. outlets, until an American senator repeated the claim on national television. As is typical, there was a kernel of truth — rare cases of heart inflammation — that purveyors of disinformation exaggerated into a global myth.

That example captures our new reality: online falsehoods can leap borders, mutate, and re-emerge in parliaments and news conferences.

My column used a simple device — the Pinocchio scale — to signal degrees of falsehood. One Pinocchio for selective truth-telling, up to four Pinocchios for outright whoppers. It became a kind of reverse restaurant review.

In the early years, the ratings were evenly distributed. Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush — they all earned Four Pinocchios about fifteen percent of the time.

Politicians might exaggerate, but they generally stayed tethered to facts. When confronted with a bad rating, most dropped the talking point. Campaigns even used fact-checks internally to keep themselves honest.

There were occasional outliers. Representative Michele Bachmann of Minnesota was a frequent visitor to the Four-Pinocchio club, and Joe Biden had his share of numerical stumbles. But these were exceptions. Even in the 2012 campaign, both Obama and Romney took fact-checking seriously. Obama’s team once protested that our Pinocchios were undermining their message — but they changed statistics that caused problems. Romney’s campaign often did the same.

That was the culture of truth a decade ago: politicians disliked being caught in a falsehood and wanted to avoid the embarrassment of being publicly corrected. Fact-checking mattered because credibility mattered.

Back then, the energy was palpable. Fact-checkers were springing up in Argentina, South Africa, India, and South Korea. Chequeado in Buenos Aires inspired others across Latin America. Full Fact in London held news outlets to account. StopFake in Ukraine battled Russian propaganda. It felt like a new frontier for journalism — a global “factcheckathon.”

Then came Donald Trump.

I had never encountered a politician so unconcerned with factual accuracy. During his first campaign in 2016 he earned Four Pinocchios roughly sixty-five percent of the time. In his first term, the pace only accelerated. He claimed that millions of undocumented immigrants voted, that Barack Obama wiretapped him, that he had passed the biggest tax cut in U.S. history. None of it was true.

He repeated falsehoods relentlessly — hundreds of times. At The Washington Post, we tracked them all. By the end of his first term we had catalogued 30,573 false or misleading claims — an average of 21 a day. By his final year, he was averaging 39 a day.

What was most striking was how the nation adjusted to it. Repetition dulled the shock. Lies became expected, even normalized. By his second term, there was little point in counting; people had stopped caring.

Trump rose at the same time social media reached critical mass. The Fact Checker launched in 2007, when Facebook had 50 million users. By 2015, it had 1.6 billion. Twitter gave Trump a direct channel to millions, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. His proposed Muslim ban was the most-shared campaign moment on Facebook that year.

Social media amplified falsehoods faster than fact-checkers could respond. Russian operatives exploited that dynamic in 2016, flooding feeds with fabricated stories. Tech companies eventually enlisted fact-checkers to label misinformation — but the political backlash was fierce. Leaders who benefited from the chaos framed it as censorship.

And now, many of those same platforms are retreating from the fight, often because of pressure from the current American administration.

Trump’s rhetoric that mainstream news organizations are “enemy of the people” and his constant attacks on “fake news” echoed far beyond the United States. Leaders in Hungary, Turkey, the Philippines, and Brazil — under former president Bolsonaro — borrowed that language to delegitimize journalists and sow distrust.

The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol was live-streamed and dissected worldwide. One year later, a near-carbon copy unfolded in Brasília. False claims about Brazil’s election, amplified by some of the same American figures who questioned Trump’s loss, spread through WhatsApp and Telegram groups and inspired the violence that day.

Bolsonaro was recently convicted for his role in the attempted coup. The current Brazilian government insists it will not bow to pressure from Trump to soften oversight of social-media platforms such as X. One Brazilian justice put it succinctly: “Your freedom does not mean being free to go the wrong way and crash into another car.” Self-regulation, she said, has proven a failure.

In Europe, debates about regulating platforms are entangled with trans-Atlantic politics. Officials fear being accused of censorship if they act too forcefully — and of negligence if they don’t. Meanwhile, conspiracy movements that began in one country migrate effortlessly to another, translated overnight into new languages and contexts.

Some European officials have acknowledged the potential danger posed by social media networks controlled by non-Europeans. French President Macron said last month: “We have been incredibly naive in entrusting our democratic space to social networks that are controlled either by large American entrepreneurs or large Chinese companies, whose interests are not at all the survival or proper functioning of our democracies.”

Another threat is the rise of generative AI. Google AI Overview and information chat bots are killing traffic to established news websites like The Washington Post, eroding an economic foundation that was built on search clicks. Few people click to read the sources on which AI builds its summary answers.

The statistics are astonishing. Ten years ago, every two Google searches would result in one click on a website; by the start of this year, it took six Google searches to get one click. With Google’s AI Overview, it now takes 18 searches for one click. It’s even worse with ChatGPT, where it takes almost 400 queries to result in one click.

As a result, organic traffic has plummeted from more than 2.3 billion visits in mid-2024 to fewer than 1.7 billion in mid-2025, with some news organizations suffering double-digit declines in traffic in just a few months. That has led to layoffs and buyouts at many news organizations.

I saw the internal numbers when I still worked at The Post. The so-called Trump bump that the newspaper received in his first term had become a slump in his second term, even though his administration was generating more news than ever.

The danger is that AI based on large language models relies on accurate information to produce its answers — and if it can’t find anything, it hallucinates answers because it must always provide an answer. There’s a possibility of a vicious circle — if news organizations wither, the quality of AI will degenerate too.

Foreign actors also exploit AI. Russia has created an effort called the Pravda Network — a collection of 150 websites that targets 49 countries in dozens of languages. A NewsGuard report this year found the ten largest AI tools on average spread Russian false claims one-third of the time when prompted by the network. That’s because the Russian program infects the AI models with so many false stories that the AI models then rely on and repeat as true.

A few weeks ago, for instance, a Republican member of Congress repeated Russian disinformation claiming Ukrainian president Zelensky was stashing $20 million month in a Middle East bank account. She’d read it in a Bing AI summary. And then of course Russian newspapers were able to report that an American lawmaker had stated this so-called fact.

Since I left The Post, I have been working with an organization called Sourcebase.ai which only relies on verified sources, such as official documents, news organization archives or fact checks produced by verified fact-checking organizations. So there are no hallucinations. The hope is that we can offer an alternative to LLMs — and possibly a way to monetize that information.

The disinformation ecosystem is global. But so, thankfully, is the resistance to it.

All this makes the core mission of fact-checking — establishing an agreed set of facts — far harder. Human psychology compounds the problem.

Studies show that people are receptive to information that confirms their pre-existing views. One experiment gave participants identical sets of numbers — one about a skin-cream study, another about gun control, the third about climate change. When the topic was neutral, both liberals and conservatives interpreted the math correctly. When it was political, accuracy collapsed; people simply made the numbers fit their side of the argument.

Another study found that two-thirds of Americans were uninterested in hearing opposing views, even when offered money to do so. A 2018 experiment discovered that exposure to tweets from political opponents for just a month made participants more polarized, not less.

In fact, in the United States, party identification has become a basic, essential sign of character. In 1960, a survey found that only 4 percent of Democrats or Republicans said they would be disappointed if their child married someone from the opposite political party. Six decades later, a survey found 45 percent of Democrats and 35 percent of Republicans said they would be unhappy if their son or daughter married someone from the other party. Strikingly, a child’s decision to marry someone from a different race, ethnicity or religion raised far less concern.

I’ve seen this firsthand. Criticize Bernie Sanders’s facts and the left attacks. Fact check a Republican and the right piles on. Increasingly, those attacks are personal — aimed not at the argument but at the journalist.

We also see a shift in public values. A decade ago, large majorities of Americans — Republicans, Democrats, and independents — said honesty was essential in a president. By 2018, that share among Republicans had fallen more than twenty points. Many decided dishonesty was acceptable if it served a higher purpose.

When truth becomes optional, democracy becomes negotiable.

In recent years, governments have turned their fire on fact-checkers themselves. In the Philippines, Rappler fought costly legal battles to survive. In Mexico, the government created its own “fact-checking” unit — not to correct falsehoods but to attack reporters.

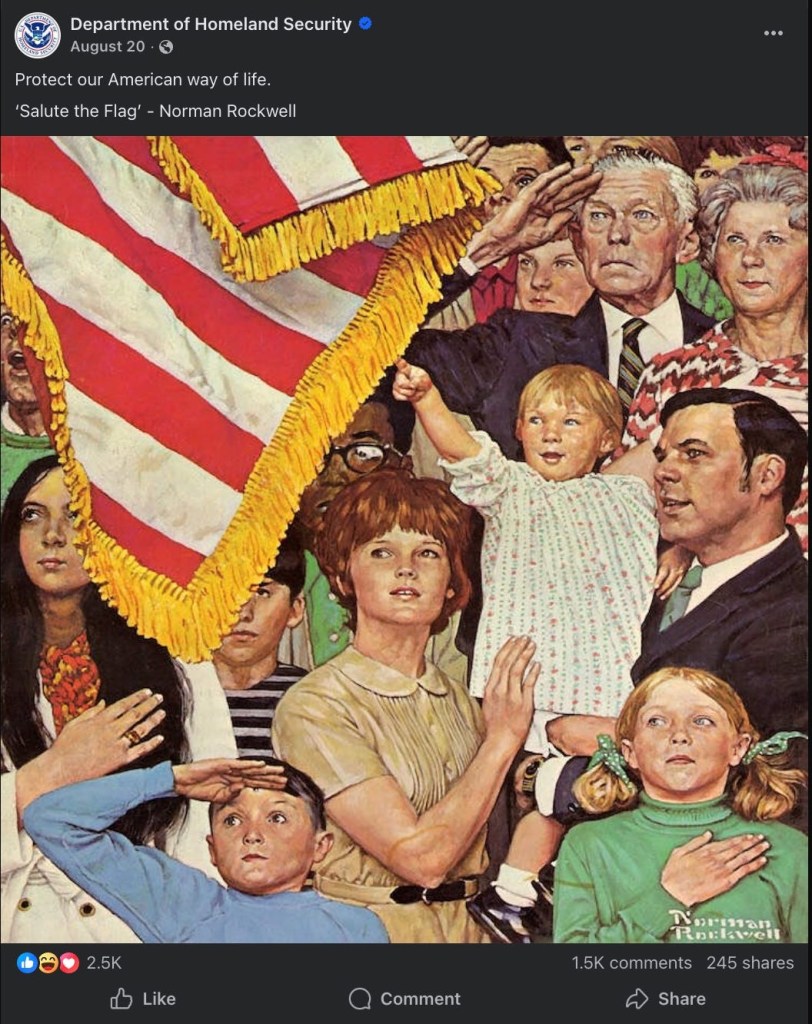

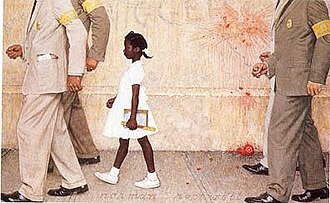

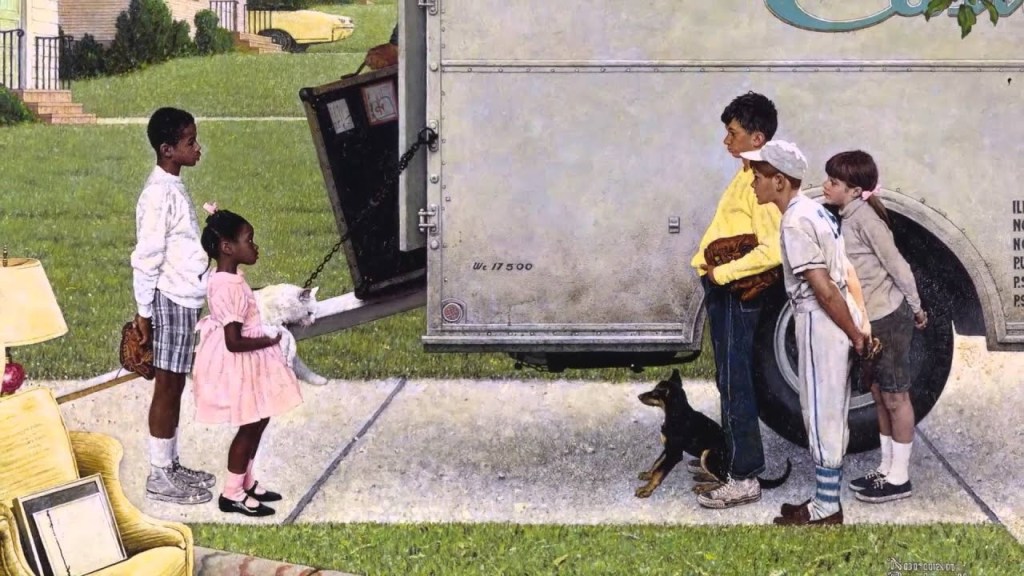

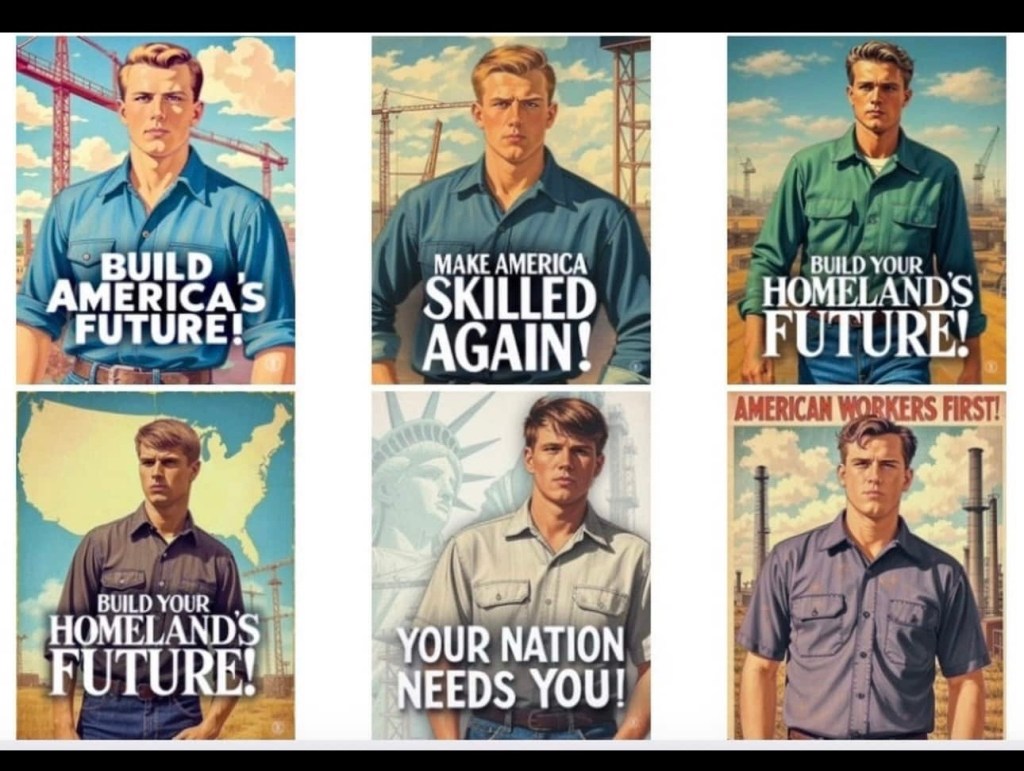

Even once-respected institutions have joined the fray. The U.S. State Department recently claimed that “thousands” of Europeans had been convicted merely for criticizing their governments — a statement unsupported by evidence. The Homeland Security Department now routinely releases viral — and misleading — videos on immigration, with dramatic footage of alleged failures and violence that happened under Biden. But some of the film was recorded during Trump’s first term — or shows events from other cities. The errors were identified by reporters — but the administration did not remove or correct the videos.

As official bodies repeat distortions once confined to the fringe, the ground beneath us shifts.

At the start of my career forty years ago, reporters could still assume a shared factual baseline. Now every claim — no matter how well-sourced — is instantly questioned by someone quoting a meme.

I’ve seen the growth and contraction of funding for fact-checking. I’ve helped build international standards only to watch them dismissed as “politically biased.” I’ve tracked 30,000 falsehoods from one U.S. president and seen millions celebrate him for it.

And yet I’ve also seen the bravery of colleagues around the world who keep checking facts under threats far greater than a Twitter pile-on. They remind me that truth is not an abstraction; it’s a public service, sometimes even an act of courage.

One reason misinformation spreads so easily is that its authors have no standards. Fact-checkers do. We document sources, explain reasoning, and publish corrections. The other side can fabricate freely. And when we make a rare mistake, that single lapse is weaponized to discredit the entire field.

Not long ago, a partisan website falsely claimed fact-checkers had made political donations — a violation of our ethics code. The allegation was baseless but was retweeted by Elon Musk to millions of followers. It’s a perfect illustration of the asymmetry: accountability for one side, none for the other.

Still, our transparency is our strength. The antidote to cynicism is openness. Explain what you checked, how you checked it, and what you found — again and again, even when you’re tired of repeating it.

Technology has brought enormous benefits. Information is democratized as never before. But it has also shattered the shared public square. Newspapers and evening newscasts once gave citizens a common set of facts. Now we curate our own realities — our own feeds, our own algorithms, our own truths.

We seem richer in information, but poorer in understanding. Sometimes it feels as if the more data we have, the less we agree on what any of it means.

I always urge people to diversify what you read and follow. If you’re a liberal, read some conservatives. If you’re a conservative, read liberals. Seek out voices that challenge your assumptions. It’s the only antidote to the intellectual isolation that algorithms create.

In my nearly three decades at The Washington Post, I wrote or edited some 3,000 fact-checks. I’ve seen the best and worst of public discourse. I’ve seen how a single fact check can change a debate — and how a dozen fact checks can still be drowned out by a lie that confirms what people want to believe.

The fight for truth has never been easy, and it will not get easier. Our goal should not to try to eliminate falsehoods — that’s impossible — but to make truth visible, persistent, and credible enough to matter.

Fact-checking may feel like pushing a rock up a hill, but every verified claim, every contextual note, every correction is a brick in the foundation of civic trust. We are not just checking facts; we are defending the conditions that make democracy possible.

This is the war on truth. It’s not a war we chose, but it’s one we cannot afford to lose.