Nick Covington taught social studies for a decade. He recently decided to delve into the mystique of “the science of reading.” He concluded that we have been “sold a story.”

He begins:

Literacy doesn’t come in a box, we’ll never find our kids at the bottom of a curriculum package, and there can be no broad support for systemic change that excludes input from and support for teachers implementing these programs in classrooms with students.

Exactly one year after the final episode of the podcast series that launched a thousand hot takes and opened the latest front of the post-pandemic Reading Wars, I finally dug into Emily Hanford’s Sold A Story from American Public Media. Six episodes later, I’m left with the ironic feeling that the podcast, and the narrative it tells, missed the point. My goal with this piece is to capture the questions and criticisms that I have not just about the narrative of Sold A Story but of the broader movement toward “The Science of Reading,” and bring in other evidence and perspectives that inform my own. I hope to make the case that “The Science of Reading” is not a useful label to describe the multiple goals of literacy; that investment in teacher professionalization is inoculation against being Sold A Story; and that the unproductive and divisive Reading Wars actually make it more difficult for us to think about how to cultivate literate kids. The podcast, and the Reading Wars it launched, disseminate an incomplete and oversimplified picture of a complex process that plasters over the gaps with feverish insistence.

Sold a Story is a podcast that investigates the ongoing Reading Wars between phonics, whole language, balanced literacy, and “The Science of Reading.” Throughout the series, listeners hear from teachers who felt betrayed by what school leaders, education celebrities, and publishers told them was the right way to teach, only to later learn they had been teaching in ways deemed ineffective. The story, as I heard it, was that teachers did their jobs to the best of their personal ability in exactly the ways incentivized by the system itself. In a disempowered profession, the approaches criticized in the series offered teachers a sense of aspirational community, opportunities for training and professional development, and the prestige of working with Ivy League researchers. Further, they came with material assets – massive classroom libraries and flexible seating options for students, for example – that did transform classroom spaces.

Without the critical toolkit and systemic support to evaluate claims of effectiveness, and lacking collective power to challenge the dictates of million dollar curriculum packages, teachers taught how they were instructed to teach using the resources they were required to use. And given the scarcity of educational resources at the disposal of most individual teachers, it’s easy to see why they embraced such a visible investment in reading instruction. Instead of seeing teachers in their relation to systemic forces – in their diminished roles as curriculum custodians – Hanford instead frames teachers who participated in these methods as having willingly bought into a cult of personality, singing songs and marching under the banners of Calkins and Clay; however, Hanford also comes up short in offering ways this story could have gone differently or will go differently in the future.

A key objective of Sold A Story is to communicate to listeners that “The Science of Reading” is the only valid, evidence-based way to teach kids to read and borders on calling other approaches a form of educational malpractice, inducing a unique pedagogical injury. In the wake of Sold A Story, “The Science of Reading” itself has been co-opted as a marketing and branding label. States and cities have passed laws requiring “The Science of Reading,” sending school leaders scrambling to purchase new programs and train teachers to comply with the new prescription.

In May 2023, the mayor of New York City announced “a tectonic shift” in reading instruction for NYC schools. The change required school leaders to choose from one of three pre-approved curriculum packages provided by three different publishing companies. First-year training for the new curriculum was estimated to cost $35 million, but “city officials declined to provide an estimate of the effort’s overall price tag, including the cost of purchasing materials.” NYC Schools also disbanded their in-house literacy coaching program over the summer to contract instead with outside companies to provide coaching. It’s hard not to conclude that the same publishing ecosystem that sold school leaders and policy-makers on the previous evidence-based reading curriculum – and that Hanford condemns in the podcast – is happy to meet their current needs in the marketplace. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Now, months into the new school year and just weeks before Winter Break, how is the hurried rollout of the new reading curriculum going for NYC schools and teachers? One Brooklyn teacher told Chalkbeat they still hadn’t received the necessary training to use the new materials, “The general sentiment at my school is we’re being asked to start something without really knowing what it should look like, I feel like I’m improvising — and not based on the science of reading.” A third-grade teacher said phonics had not been the norm for her class, and that she hasn’t “received much training on how to deliver the highly regimented lessons.” Other teachers echo the sentiment of feeling rushed, hurried, and unprepared. One 30+ year veteran classroom teacher mentioned that she has “turned to Facebook groups when she has questions.” The chaotic back-and-forth was also recognized by many veteran teachers responding to the Chalkbeat piece on social media. One education and literacy coach commented, “I sometimes wonder how many curriculum variations I’ve seen in the last 3 decades – ’Here teachers [drops off boxed curriculum], now teach this way’ – hasn’t changed student outcomes across systems.”

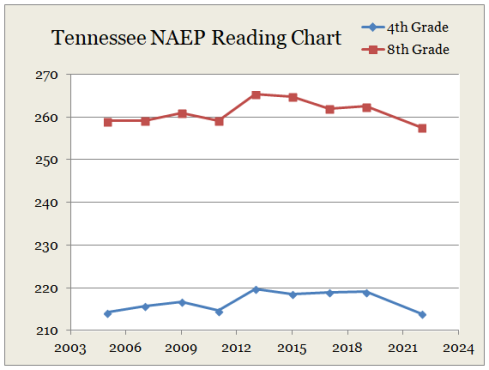

Open the post to read Covington’s review of the research on phonics-based programs. No miracle. No impressive rise in test scores.

Most of my professional career has been devoted to debunking “miracles“ in education. Whole language was not a miracle cure. Neither is phonics.

Why not take the sensible route? Make sure that teachers know a variety of methods when they enter the profession. Let them do what they think is best for their students. Not following the fad of the day, but using their professional knowledge.