Tom Ultican, retired teacher in California, smells a scam in the making. The science behind “the Science of Reading” movement is not very scientific, he writes. Publishers and vendors are preparing to cash in on legislative mandates that force reading teachers to use only one method to teach reading despite the lack of evidence for its efficacy. Ultican zeroes in on the role of billionaire Laurene Powell Jobs as one of the key players in promoting SofR.

He writes:

Laurene Powell Jobs controls Amplify, a kids-at-screens education enterprise. In 2011, she became one of the wealthiest women in the world when her husband, Steve, died. This former Silicon Valley housewife displays the arrogance of wealth, infecting all billionaires. She is now a “philanthropist”, in pursuit of both her concerns and biases. Her care for the environment and climate change are admiral but her anti-public school thinking is a threat to America. Her company, Amplify, sells the antithesis of good education.

I am on Amplify’s mailing list. April third’s new message said,

“What if I told you there’s a way for 95% of your students to read at or near grade level? Maybe you’ve heard the term Science of Reading before, and have wondered what it is and why it matters.”

Spokesperson, Susan Lambert, goes on to disingenuously explain how the Science of Reading (SoR) “refers to the abundance of research illustrating the best way students learn to read.”

This whopper is followed by a bigger one, stating:

“A shift to a Science of Reading-based curriculum can help give every teacher and student what they need and guarantee literacy success in your school. Tennessee school districts did just that and they are seeing an abundant amount of success from their efforts.”

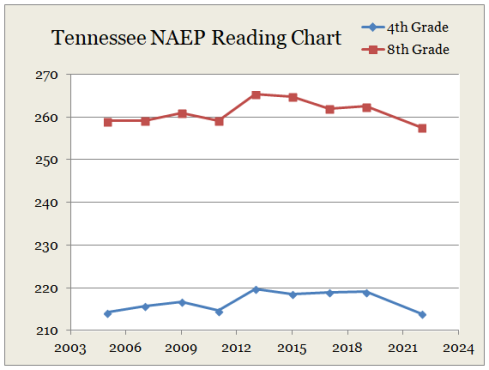

A shift to SoR-based curriculum is as likely to cause harm as it is to bring literacy success. This was just a used-car salesman style claim. On the other hand, the “abundance of success” in Tennessee is an unadulterated lie. National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) tracks testing over time and is respected for education testing integrity. Tennessee’s NAEP data shows no success “from their efforts.” Their reading scores since 2013 have been down, not a lot but do not demonstrate an “abundance of success”.

NAEP Data Plot 2005 to 2022

Amplify’s Genesis

Larry Berger and Greg Dunn founded Wireless Generation in 2000 to create the software for lessons presented on screens. Ten years later, they sold it to Rupert Murdoch and his News Corporation for $360 million. Berger pocketed $40 million and agreed to stay on as head of curriculum. Wireless Generation was rebranded Amplify and Joel Klein was hired to run it.

Murdoch proposed buying a million I-pads to deliver classroom instruction. However, the Apple operating system was not flexible enough to run the software. The android system developed at Google met their needs. They purchased the Taiwanese-made Asus Tablets, well regarded in the market place but not designed for the rigors of school use. Another issue was that Wireless Generation had not developed curriculum but Murdoch wanted to beat Pearson and Houghton Mifflin to the digital education market place … so they forged ahead.

In 2012, the corporate plan was rolling along until the wheels came off. In Guilford County, North Carolina, the school district won a Race to the Top grant of $30 million dollars which it used to experiment with digital learning. The district’s plancalled for nearly 17,000 students in 20 middle schools to receive Amplify tablets. When a charger for one of the tablets overheated, the plan was halted. Only two months into the experiment, they found not only had a charger malfunctioned but another 175 chargers had issues and 1500 screens were kid-damaged.

This was the beginning of the end.

By August of 2015, News Corporation announced it was exiting the education business. The corporation took a $371 million dollar write-off. The next month, they announced selling Amplify to members of its staff. In the deal orchestrated by Joel Klein, who remained a board member, Larry Berger assumed leadership of the company.

Three months later, Reuters reported that the real buyer was Laurene Powell Jobs. She purchased Amplify through her LLC, the Emerson Collective. In typical Powell Jobs style, no information was available for how much of the company she would personally control.

Because Emerson Collective is an LLC, it can purchase private companies and is not required to make money details public. However, the Waverley Street Foundation, also known as the Emerson Collective Foundation, is a 501 C3 (EIN: 81-3242506) that must make money transactions public. Waverly Street received their tax exempt status November 9, 2016.

SoR A Sales Scam

The Amplify email gave me a link to two documents that were supposed to explain SoR: (Navigating the shift to evidence-based literacy instruction 6 takeaways from Amplify’s Science of Reading: The Symposium) and (Change Management Playbook Navigating and sustaining change when implementing a Science of Reading curriculum). Let’s call them Symposium and Navigating.

Navigating tells readers that it helps teachers move away from ineffective legacy practices and start making shifts to evidence-based practices. The claim that “legacy practices” are “ineffective” is not evidence-based. The other assertion that SoR is evidence-based has no peer-reviewed research backing it.

Sally Riordan is a Senior Research Fellow at the University College London. In Britain, they have many of the same issues with reading instruction. In her recent research, she noted:

“In 2023, however, researchers at the University of Warwick pointed out something that should have been obvious for some time but has been very much overlooked – that following the evidence is not resulting in the progress we might expect.

“A series of randomised controlled trials, including one looking at how to improve literacy through evidence, have suggested that schools that use methods based on research are not performing better than schools that do not.”

In Symposium, we see quotes from Kareem Weaver who co-founded Fulcrum in Oakland, California and is its executive director. Weaver also was managing director of the New School Venture Fund, where Powell Jobs served on the board. He works for mostly white billionaires to the detriment of his community. (Page 15)

Both Symposium and Navigating have the same quote, “Our friends at the Reading League say that instruction based on the Science of Reading ‘will elevate and transform every community, every nation, through the power of literacy.”’

Who is the Reading League and where did they come from?

Dr. Maria Murray is the founder and CEO of The Reading League. It seems to have been hatched at the University of Syracuse and State University of New York at Oswego by Murray and Professor Jorene Finn in 2017. That year, they took in $11,044 in contributions (EIN: 81-0820021) and in 2018, another $109,652. Then in 2019, their revenues jumped 20 times to $2,240,707!

Jorene Finn worked for Cambria Learning Group and was a LETRS facilitator at Lexia. That means the group had serious connections to the corporate SoR initiative before they began.

With Amplify’s multiple citations of The Reading League, I speculated that the source of that big money in 2019 might have been Powell Jobs. Her Waverly Street Foundation (AKA Emerson Collective Foundation) only shows one large donation of $95,000,000 in 2019. It went to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation (EIN: 20-5205488), a donor-directed dark money fund.

There is no way of following that $95 million.

The Reading League Brain Scan Proving What?

Professor Paul Thomas of Furman University noted the League’s over-reliance on brain scans and shared:

“Many researchers in neurobiology (e.g., Elliott et al., 2020; Hickok, 2014; Lyon, 2017) have voiced alarming concerns about the validity and preciseness of brain imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to detect reliable biomarkers in processes such as reading and in the diagnosis of other mental activity….

“And Mark Seidenberg, a key neuroscientist cited by the “science of reading” movement, offers a serious wcaution about the value of brain research: “Our concern is that although reading science is highly relevant to learning in the classroom setting, it does not yet speak to what to teach, when, how, and for whom at a level that is useful for teachers.”

“Beware The Reading League because it is an advocacy movement that is too often little more than cherry-picking, oversimplification, and a thin veneer for commercial interests in the teaching of reading.”

The push to implement SoR is a new way to sell what Amplify originally called “personalized learning.”This corporate movement conned legislators, many are co-conspirators, into passing laws forcing schools and teachers to use the SoR-related programs, equipment and testing.

SoR is about economic gain for its purveyors and not science based.

When politicians and corporations control education, children and America lose.

To read an earlier post by Tom Ultican on this topic, see this.