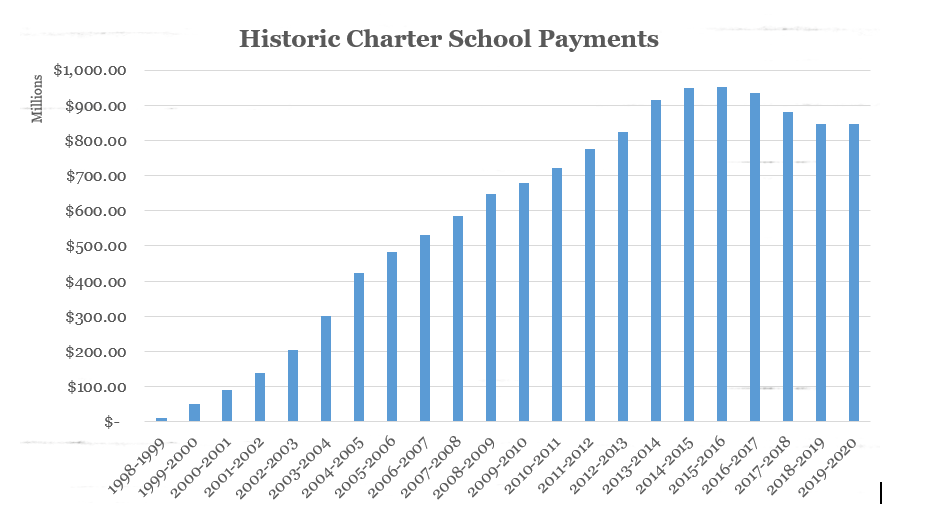

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute released a report on Ohio charters, claiming that they were very successful. (TBF is a rightwing organization that supports charters and vouchers.) The Columbus Dispatch wrote that the report demonstrated that charter schools in Ohio are more successful than the state’s public schools. But Stephen Dyer reviewed the report and concluded that its findings are based on cherrypicking schools and manipulating data. In fact, he writes, Ohio’s charter sector continues to be low-performing compared to the state’s public schools, whose students lose funding to charters. The state has recently taken almost $900 million annually from its public schools to pay for a mediocre charter sector.

Dyer is a former state legislator who has written often about the charter industry. He is now Director of Government Relations, Communications and Marketing at the Ohio Education Association. (I served on the board of the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation/Institute from 1998-2009).

He writes:

Fordham Strikes Again

Cherry picking schools; manipulating data; grasping at straws

Look, the Fordham Institute has been improving lately, calling for more charter school oversight and talking a good game. But I guess sometimes old habits die hard, and in Ohio – the cradle of the for-profit charter school movement – those habits tend to linger especially long.

Take the group’s latest report – The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes, 2016-2019 – is yet another attempt to make Ohio’s famously poor performing charter school sector seem not quite as bad (though I give them kudos for admitting the obvious – that for-profit operators don’t do a good job educating kids and we need continued tougher oversight of the sector).

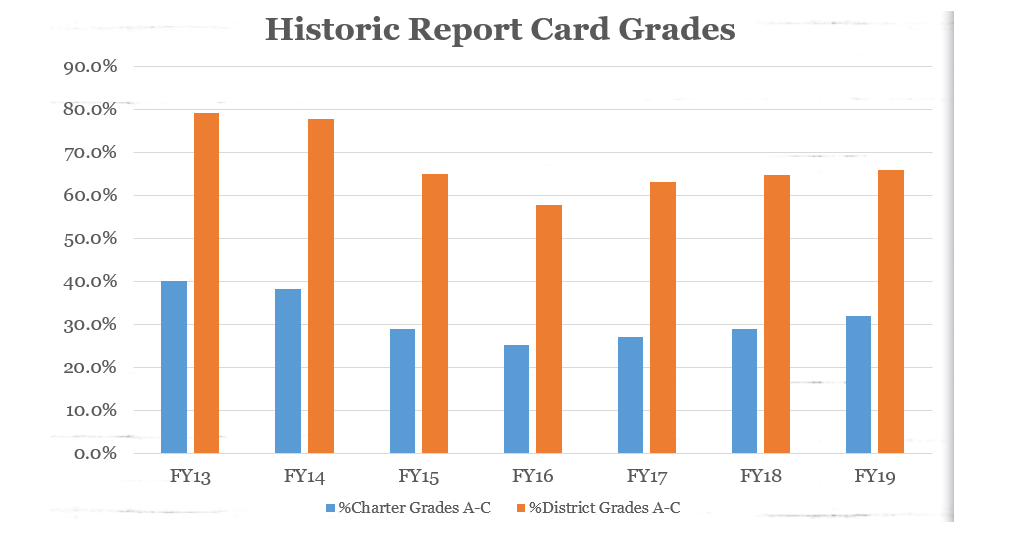

But folks, really. On the whole, Ohio charter schools are not very good. For example, of all the potential A-F grades charters could have received since that system was adopted in the 2012-2013 school year, Ohio charter schools have received more Fs than all other grades combined.

So how could the Fordham report claim, as the Columbus Dispatch headline writers put it: “Students at Ohio charter schools show greater academic gains”?

Simple.

Fordham ignored all but a fraction of the Ohio charter schools in operation during the FY16-FY19 school years, including Ohio’s scandalously poor performing e-schools (yes, ECOT was still running then), the state’s nationally embarrassing dropout recovery charter schools (which have difficulty graduating even 10 percent of their students in 8 years), and the state’s special education schools – some of whom have been cited for habitually billing taxpayers for students they never had.

In other words, they only looked at the best possible charter clusters in the state. And even though they essentially ignored the worst actors in the state (effectively ignoring how more than ½ of all charter students perform), the “performance gains” they point to are not impressive.

For example, “Students attending charter schools from grades 4 to 8 improved from the 30th percentile on state math and English language arts exams to about the 40th percentile. High school students showed little or no gains on end-of-course exams.”

Really? A not-even-10-percentile improvement? And none in high school? That’s it?

How about this: “Attending a charter school in high school had no impact on the likelihood a student would receive a diploma.”

So we spend $828 million a year sending state money to charters that could go to kids in local public schools to have literally zero impact on attaining a diploma?

Egad.

Another problem: the report says charter students have better attendance rates. No word on whether the fact all charter students must be bused by local school districts, which in turn don’t have to bus district students, had any impact on that metric.

(Hint: it does.)

The report found better performance from charter students in at least one of the math or English standardized tests in 5 of Ohio’s 8 major urban districts (Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo and Youngstown). Only in Columbus did they outperform the district in both reading and math.

The report ignores that ECOT took more kids from Columbus in these years than any other charter school in Columbus. And, of course, those kids did far worse than Columbus students.

But even cherry picking students. And data. And methodology, Fordham only found slightly better performance in one of two tests the study examined (again, Ohio requires tests in many subjects, but I digress) in 5 urban districts, better performance in both tests in 1 and no better performance in Cincinnati and Toledo, which lost about $500 million in state revenue to charters during these 4 years the study examined.

Of course, the study also ignored that about ½ of all charter school students do NOT come from the major urban districts, including large percentages of students in many of the brick and mortar schools Fordham examined for this study. For example, about 30 percent of Breakthrough Schools students in Cleveland don’t come from Cleveland. Yet Breakthrough’s performance is always only compared with Cleveland.

Ohio charter school performance isn’t complicated. Overall, it’s really not good, especially when you look at the approximately 50 percent of students who attend online, dropout recovery or special needs schools. Are there exceptions? Of course. But here’s what the most recent data tell us:

- More than 34% of Ohio public school graduates have a college degree within 6 years. Just 12.7% of charter school graduates do

- More than 58% of Ohio public school graduates are enrolled in college within two years; only 37.2% of Ohio charter school graduates are.

Why is this important? Because if charter schools performed the same as Ohio’s public schools, 750 more charter school students would have college degrees. Why does that matter? Because a college degree will allow you to make about $1 million more during your lifetime than not having it. So it can be said that Ohio charter schools are costing Ohioans about $750 million in potential earnings, just from one class of students!

Some more:

- The average dropout recovery charter school has less than 0.5% of its students earning an industry recognized credential within 9 years and less than 0.2% of those students earn at least 3 dual enrollment credits within 4 years.

- In 52 of the state’s 68 dropout recovery charter schools, no kids earned at least 3 dual enrollment credits within 4 years

- In 33 of the state’s 68 dropout recovery charter schools, no kids earned an industry recognized credential within 9 years!

- In more than 1 in 5 Ohio charter schools, more than 15% of their teachers teach outside their accredited subjects

- The median percentage of inexperienced teachers in Ohio charter schools is 34.1%. The median in an Ohio public school building is 6%.

During the time period this report examined, nearly $4 billion in state money was transferred from kids in local public school districts to Ohio’s privately run charter schools. And even if you look at the very best slice of the mud pie that is Ohio’s charter school sector, you get perhaps modest gains – not even 10 percentiles worth though – in a few of the schools.

But that didn’t stop Fordham from excitedly declaring at the beginning of its report that this study demonstrates that “Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters have proven themselves capable of providing quality options—and it’s time to give families across the state similar opportunities.” Or that “high-quality” charters should be expanded.

One more dirty little secret about “high-quality” charters? Historically, the “high-quality” school buildings in Ohio’s major urban districts actually outperform the “high-quality” charter schools in those districts.

So maybe the answer, especially during this pandemic, is expanding “high-quality” local public school buildings, or investing at least some of the $828 million currently being sent to Ohio’s mostly poor performing charter schools back to local public schools so they have a better shot at being dubbed “high quality”, thereby expanding the number of “high-quality” options for students?

Just a thought…