In the bizarro world of charters in Pennsylvania, the receiver of a bankrupt district (Chester Upland) granted a nine-year renewal to a low-performing charter school (The Chester Community Charter School), pushing millions towards its sponsor.

The charter enrolls 70% of the primary school students in the district. It has been the prime mover in bankrupting the district, drawing away resources and students. In exchange for not opening a high school (which it did not plan to do), the receiver gave it another nine more years.

What is behind this sweet deal?

The owner of the school was one of the biggest contributors to former Republican Governor Tom Corbett and a member of his transition team.

He has profited handsomely by supplying goods and services to his Chester Community Charter School.

CSMI’s founder and CEO is Vahan H. Gureghian of Gladwyne, a lawyer, entrepreneur and major Republican donor –the largest individual contributor to former Gov. Tom Corbett. And though CSMI’s books are not public – the for-profit firm has never disclosed its profits and won’t discuss its management fee – running the school appears to be a lucrative business. State records show that Gureghian’s company collected nearly $17 million in taxpayer funds just in 2014-15, when only 2,900 students were enrolled.

The receiver is a Republican accountant who served as treasurer of Corbett’s campaign.

State Auditor General Eugene DePasquale, whose office has scrutinized the Chester school’s finances in the past and who has often called the state’s charter law “the worst in the country,” was unaware of the renewal until he was told this month by the Inquirer and Daily News.

DePasquale, a Democrat, said he had never heard of such a lengthy charter school renewal, and questioned whether the move limited the district’s authority to demand improvements, especially at a school where test scores are so low.

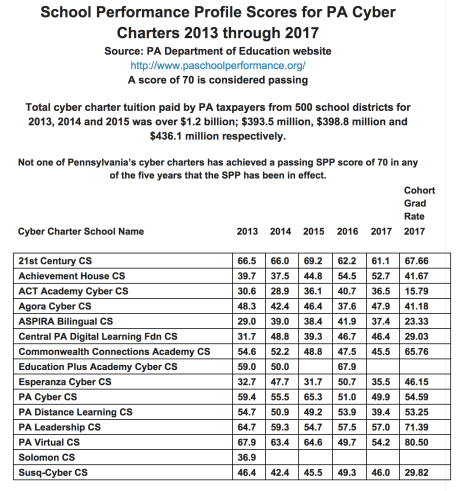

Things are going well on the financial side for the charter company, but not so well on the academic front. Its schools have shown very low performance. But poor academic performance is no deterrent to its longevity or its profitability!

CSMI, its parent company, has long been a prominent player in the charter world – and not just in Chester. The company runs a school in Atlantic County, N.J., and until last year had another in Camden – New Jersey denied its renewal because of low academic performance.

Chester Community has also struggled to succeed. The Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) exams released in September showed that Chester Community had some of the lowest scores among charter schools in the region: Less than 16 percent of students passed PSSA reading tests in the last school year; 6 percent passed math.

The scores were lower than all but one of the four Chester Upland district schools that have K-8 students.

When the State Education Department tried to remove the receiver of the district, who has the same powers as a superintendent, Chester Community Charter School defended him, and he held on to his position.

Two weeks after the receiver was reappointed, the charter school filed its request for a nine-year extension and the receiver agreed.

By the way, the charter founder-owner has dropped the price of his Palm Beach mansion to only $64.9 million. It is a steal It is almost a $20 million drop from the original asking price.

The owners of a never-occupied, eight-bedroom mansion in Palm Beach cut their asking price by $5 million to $64.9 million.

The new $64.9 million asking price for the French Chateau-style mansion is almost $20 million below the original asking price when it was listed for sale more than two years ago.

The 35,993-square-foot residence at 1071 North Ocean Boulevard is still the most expensive home listed in the Palm Beach Board of Realtors Multiple Listing Service…

The owner is a trust linked to Philadelphia-area lawyers Vahan and Danielle Gureghian, who initially planned to occupy the custom-built home.

The Gureghians’ Palm Beach residence features a bowling alley, home theater, pub room and library, plus dual ocean balconies and an eight-car garage.