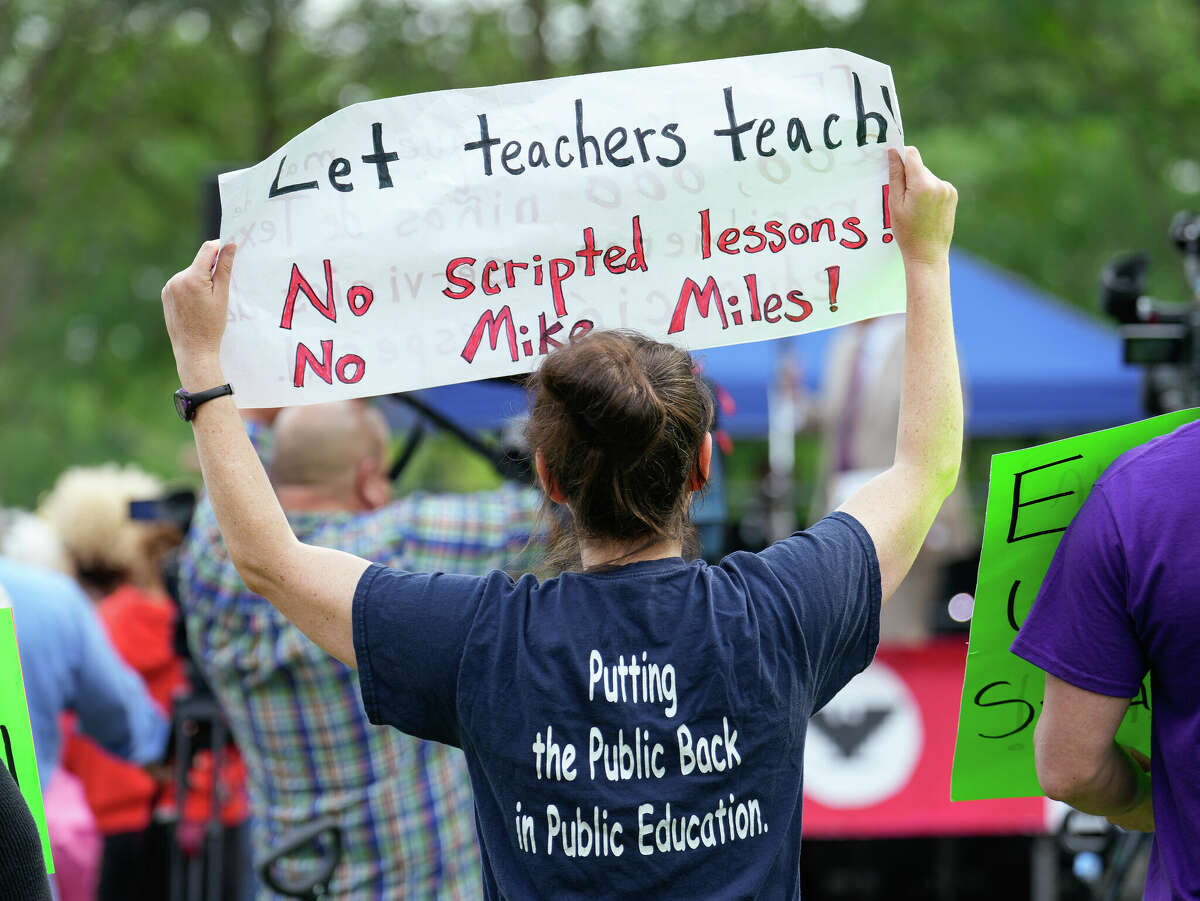

School started in the Houston Independent School District, and many teachers were stunned by the extent to which their actions were constrained by a script. The new superintendent Mike Miles has be never been a teacher but he thinks he knows everything about teaching. He laid down strict rules, and teachers must comply without hesitation. Miles is the kind of leader who, if put in charge of a hospital, would tell surgeons how to conduct surgeries. This story appeared in the Houston Chronicle and was written by staff writer Anna Bauman.

As she prepared for the start of a new school year in Houston ISD, a fifth-grade reading teacher stripped much of the colorful personality from her classroom, including motivational posters, student art projects, several bins of books and a social-emotional learning nook with comfy furniture.

She wiped away tears and, earlier this week, started teaching at a school under the New Education System, a wholesale reform model introduced by Superintendent Mike Miles, who was appointed in June by the Texas Education Agency to run the largest school system in Texas.

While parents and students may have noticed few of the changes, educators from a wide swath of schools in HISD say they feel micromanaged and stressed in their first week under new district leaders, who are reportedly enforcing strict guidelines and conducting frequent classroom observations that have sparked frustration, fear and low morale among teachers at both NES and non-NES schools.

“I feel like they are not allowing me to do what’s in the best interest of the children,” said the reading teacher. “Every day I go to work, I’m crying. Every day I leave from work, I’m crying.”

The superintendent, meanwhile, said he has been pleased with what he has seen while collecting a “baseline” at NES schools in the first week.

“I was very impressed with their progress, even in one day, but also their preparation for the beginning of the school year,” Miles said. “Teachers were teaching well, they were following the instructional model, and it was pretty good. It shows that the schools and the teachers have been preparing hard for the first day, second day of school.”

The district is laying the groundwork for a pay-for-performance evaluation system geared toward measuring the quality of a teacher’s instruction, although a Harris County judge has temporarily blocked HISD from implementing the system.

“The high-quality instruction, there’s a clear rubric for that, there’s a clear spot observation form, because we have to train teachers,” Miles said. “We can’t just do what we’ve always done, which is go into a classroom every three weeks or three months and think we’re going to see something that is effective teaching, and just rely on, ‘Oh, I’ll know it when I see it.’”

This year, all principals will be evaluated under a new system that requires them to give instructional feedback and spend significant time coaching teachers in classrooms. Principals will be graded in part based on the quality of instruction at their school. Meanwhile, teachers will also be measured with a new evaluation system this year, although those who do not work in the schools targeted for reform may ask for a waiver.

District leaders trained teachers in recent weeks on the evaluation system and new classroom expectations. For example, one slideshow presented during teacher training listed some “common practices that we want to generally avoid,” including stream of consciousness writing, rooms with dim lighting and worksheets that are not purposeful. The training materials also discouraged teachers from showing entire films, letting kids “earn” free time and allowing “poor readers” to read aloud during class.

The slideshow instructed teachers to post a “lesson objective” on the board before the start of each class, avoid wasting time on transitions between activities, teach “bell to bell,” teach grade-level content to “every student every day” and use a timer to guide pacing of the lesson. Teachers should use a “multiple response strategy,” an activity that engages and checks the understanding of all students, every four minutes, according to a sample spot observation form.

On the first day, teachers said they were expected to skip introductions and get-to-know-you games, instead jumping right away into instructional material.

“I don’t even know who my kids are because we haven’t been able to get to know them,” said the fifth-grade reading teacher. “They still call me ‘teacher’ because they can’t remember my name.”

She has struggled to stay on pace with the timed lessons and was scolded for bringing in additional materials to help students, many of whom are Spanish speakers who cannot read on grade level. When she raised concerns about the fast pace, a district official told a campus administrator that the teacher was “moving too slow.”

“We’re not allowed to give them work on a level they understand. Most of the time, they sit there confused,” the teacher said. “I’ve had students crying since day two, saying they’re overwhelmed.”

Meanwhile, Jessica Waligorski, a special education support teacher at Isaacs Elementary School, said she appreciates the rigor, high expectations and organization of the NES model. Administrators are supportive and easily accessible at her NES campus, she said. Teachers lift each other up when doubts creep in and students have taken to the new model “like sponges,” she said.

“Everyone is holding each other to a standard and we’re not wavering,” she said. “We have set the tone, we have set expectations, we have set goals … and our kids have been engaged, learning. They don’t have a minute to misbehave because there’s so many things they’re learning.”

Miles has said there is no directive from the district mandating that teachers at non-NES schools teach with a specific curriculum or follow a certain instructional model. In reality, however, many of the new rules and expectations seem forced on campuses across the district, including high-performing schools that do not fall under NES.

Some of the rules seem to have been taken to an extreme. One teacher said she asked for an accommodation to use lamps instead of florescent lights in her classroom due to a serious medical condition. District officials denied her request and suggested another option: Wear sunglasses.

The teacher has already started getting headaches from the bright lights.

“I have all my lights on,” she said. “I’m trying to get through the day.”

In addition to turning on lights, the teacher, who works at a non-NES middle school, has made several other changes this year, including removing bean bag chairs from her classroom, keeping the classroom door open and following the new instructional techniques outlined on the evaluation rubric.

District staff have been observing classrooms almost every day this week, she said. The teacher said she was nervous to sit down while taking attendance or interrupt a lesson to tell a funny story during class.

“We all feel afraid to step out of line,” she said.

One teacher at a non-NES campus said she was observed by appraisers three times on Monday, creating a climate of fear and nerves even at a top-ranked campus. She loves having visitors in her classroom — “I’m a really good teacher and I’m proud of what I do” — but it feels different when “someone’s sitting there, ticking boxes,” especially on the first day of class.

“People are having trouble sleeping because they’re on edge,” she said. “It’s the constant anxiety that we’re going to be caught and that we’re going to be dinged. … I think you’re going to see a mass exodus of teachers at the end of this year, if this continues.”

One teacher at a different non-NES campus said he and other educators were chastised for spending the first day on introductions, logistics and relationship building with students rather than teaching content.

The teacher stayed three hours late that night to adjust his lesson plans for the second day, and his principal checked in first thing the next morning to make sure that he was prepared to teach a full-blown lesson, as expected by the appraiser in his classroom.

The new expectations and frequent classroom observations from district administrators this week has created a sense of frustration and anxiety on campus, according to the teacher, who said he was ready to quit even though he feels “called” to the profession.

“There’s no grace, there’s no empathy, there’s no treating people as people,” he said. “We are not encouraged to move forward — we’re pushed off the cliff and told to fly. And if you don’t fly, you fail.”

Many of the teachers at his top-rated campus have decades of experience, he said.

“I work at a really special school. … We should not be the target,” he said. “We were hoping that we’d be so far under the radar that we’d be left alone, but that’s not the case.”

Notice – no politician of note is standing up against this regime. Abbott must go!

LikeLike

Wouldn’t it be great if Texans voted out the whole gang of thieves?

LikeLike

It certainly would!

LikeLike

So is Mike Miles going to be arrested when this all comes crashing down? Is Abbot going to face prosecution when scores (O the mighty scores!) respond the same way they have elsewhere?

This is criminal.

LikeLike

The ability to cover material is not teaching. When these regimented teachers check for understanding, and they find many students are lost, what do they do in Miles’ one size fits all classrooms? I’ve taught ELLs with tremendous learning gaps. Particularly, in sequential subjects like math, it makes no sense to teach division when many students can barely add in single digits. That is why trained teachers sometimes use flexible groupings.

For struggling students it is far more efficient and effective to meet students where they are and take them where they need to go. Otherwise, there will be mass confusion among the neediest students.

In what other career would any leadership bring in someone with less training and experience and expect them to lead those that actually prepared to learn how to teach? Would a hospital bring in interns and expect them to supervise the surgeons? Would a master plumber have to report to a journeyman? Only in teaching with a female majority workforce! Miles is trained and qualified to work in the military, not education. Paternalism at its finest!

LikeLike

Retired Teacher, your analogies are not quite right. Miles is not like an intern leading a hospital. He is more like a skilled auto mechanic leading a hospital. He never taught. The little he knows about education was instilled by the failed Broad Institute.

LikeLike

Sorry, Diane. You may be right, but I perceive Miles as being a bit more like some of Trump’s cabinet appointments: designed to ruin the system they run. Miles is doing this on purpose. He is not ignorant, he is a pernicious imposter. He wants failure even as he claims success.

LikeLike

Well said, Roy.

His job is to disrupt, and he’s doing it.

LikeLike

@Diane — Thank you for featuring my personal experience in “Listen to the Kids.” You know, I have learned tremendously from the kids. As always, what worked for me, doesn’t always work for others — I just evaluated the situation, made some concessions, and moved to help kids take ownership of their education in my personal learning space. I wanted students to seek out a mentor whomever that might be, not just me. I always felt learning should be organic; throw out the bad, keep the good and learn from ALL experiences. Once again, I feel blessed you felt what I had to say was worth highlighting. Blessings.

LikeLike

And here’s to one of my favorite artists and storytellers. Ahh, oh the places one can go through art and reading and nature!” Nice news. https://nicenews.com/culture/author-illustrator-eric-carle-very-hungry-caterpillar/

LikeLike

I wonder how the military would feel about being led by teachers? It would never be done out of respect for the military, but there is no respect for teachers in right wing extremist states.

LikeLike

Indeed, there are trained solders in the military. And there are also people serving in the military. Once during a promotion interview, I was repeatedly pressed to say which was I. Soldier or server? I said server and stuck with that. Later I learned had I said solider, I would not have passed the interview. Solders, trained to always follow orders mindlessly, were not wanted in ranks of leadership.

Again, the problem with Mike Miles is Mike Miles sans the military.

LikeLike

The frustration and anxiety fueled

by unmet expectations, is as old as

the hills, as is the top-down,

dominance and submission system,

that demands INEQUALITY, in

order to exist.

Who doesn’t know, the fish rots

from the head, and if you decide

to “swim” in the pond, you do what

the rotten head commands or you

sink.

Sorry your expectations aren’t met.

Is looking for grace or empathy,

from

a dominance and submission system,

a realistic expectation?

LikeLike

From the bottom of my heart, I feel for these teachers. My son is starting a teaching career and he is so excited to make learning exciting and engaging. But to CRUSH the teachers enthusiasm like this is horrible. I know the scripted saga and the “clip board patrols” who are not evaluating, but come into your room and no matter how hard one tries, it crushes whatever teaching is going on. Do other “professionals” get treated this way?

LikeLike

Such a sad situation that promises to only get worse. But imagine for a moment the frustration of the kids when their teachers don’t appear to be making an effort to develop a relationship with them

LikeLike

In 2024, voters in Texas will have a choice: vote out the fascists running their state. If the voters don’t do that, Texas is lost unless the courts step in, and when verdicts that support democracy are ignored, send in the troops to enforce the rule of law.

Still, teachers in Texas (and other fascist red states) have a choice. Since there is a shortage of teachers in most if not all states, quit and move out of Texas to teach in a BLUE state.

I don’t think the fascist governors running Texas, or Florida, or Arkansas care if all their professional teachers quit and moved to new jobs in blue states.

The fascists would probably hire former felons who served their time. The crimes they served time for wouldn’t matter. At the top of the list for qualifications would be how dedicated they were to supporting fascism.

“The Modern Republican Party is Hurtling Toward Fascism”

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/apr/15/the-modern-republican-party-fascism-robert-reich

“Is there any fascist analog on the American left? That’s one of those rhetorical questions that’s easily disposed of. There is no such thing as fascism on the American left. There might be violence on the American left, although there’s far less than there is on the right. This is a tactical move on the right to deny its own responsibility.”

https://www.bu.edu/articles/2022/are-trump-republicans-fascists/

LikeLike

Texans could have voted for Beto. He made a great dent in the red wall of Texas, but not enough to win. He could have brought them out of the Abbott’s dark ages.

LikeLike