The Arizona Republic conducted an intensive investigation of the effort by the Trump campaign and discovered some fascinating details.

Rusty Bowers was talking on his cellphone to Karen Fann after church services on the Sunday before Thanksgiving, looking ahead to another hectic week.

It was Nov. 22, 2020. The counting was done and Joe Biden led Donald Trump by a razor-thin margin, but the presidential election results in Arizona still had not been certified.

The state’s House speaker and Senate president have a bond that stretches back decades, forged by family friendships. This time, the two Republicans conferred about something that surprised them both.

Fann told Bowers that the president’s allies had called her repeatedly. They wanted to get her involved in a plan to help deliver an election result more to his liking.

By then, it was clear to most that Trump had lost his reelection bid for the White House and that Arizona had helped elect Biden.

Seconds after Bowers hung up with Fann, and while he still sat parked in his driveway in the driver’s seat of his Toyota Prius, the dashboard on his car lit up.

Bowers had a phone call. It was the White House.

Trump and Giuliani wanted Bowers to help ensure President-elect Biden’s 10,457-vote win in Arizona would not be formalized a week later. They told him “there’s a way we could help the president” and Arizona had a “unique law” that allowed the Legislature to choose its electors, rather than voters, he recalled.

“That’s the first I’ve heard of that one,” a skeptical Bowers told them. He told the men he needed proof to back up their claims: “I don’t make these kinds of decisions just willy-nilly. You’ve got to talk to my lawyers. And I’ve got some good lawyers.”

Bowers told them he supported Trump, voted for Trump and campaigned for him, too. What he would not do is break the law for him.

“You are giving me nothing but conjecture and asking me to break my oath and commit to doing something I cannot do because I swore I wouldn’t. I will follow the Constitution,” he told the men.

Trump, who was gregarious throughout much of the call but quiet during that exchange, told Bowers he understood.

Trump told Bowers, “We’re just trying to investigate.”

Giuliani repeatedly assured Bowers he would send the evidence to attorneys at the state House of Representatives.

The evidence never arrived, Bowers told The Arizona Republic.

But Fann proceeded with the ballot review Trump wanted.

Why did this scene unfold in Arizona?

This is how Arizona plunged into a fog of conspiracies, riven with partisanship and targeted by opportunists from across the country.

Trump led the effort to undermine the results after some projected Arizona to slip to Democrat Joe Biden.

The state was one of two targeted by congressional Republicans on Jan. 6 who were willing to disenfranchise millions of voters in a brash legal experiment that would have redefined the election-certification process.

And even before Trump left the White House, Fann put in motion a ballot review.

Of the swing states, Arizona perhaps was the most susceptible to an election challenge.

Biden’s margin of victory in Arizona was the smallest of any state he won. State government was in Republican hands, providing plenty of potential allies, from the governor to the leaders of the state Legislature to the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors.

Trump, who viewed the focus on Russian interference in the 2016 election as an effort to delegitimize his victory, now heaped doubt on Biden’s win. But Trump’s loyal base didn’t see how tenuous his hold on Arizona had grown. While Trump evinced confidence at rallies, behind the scenes his campaign team knew the state was up for grabs.

Trump’s push to challenge the election results in Arizona provided balm for a man unwilling to accept defeat. It also sowed lingering doubt that would fuel an attack from people all over the country on the state’s election systems.

Many Republicans quickly joined Trump’s unfounded accusations of fraud, some more forcefully than others. A few, such as Bowers and Gov. Doug Ducey, resisted the public and political pressure to get behind the narrative of a stolen election.

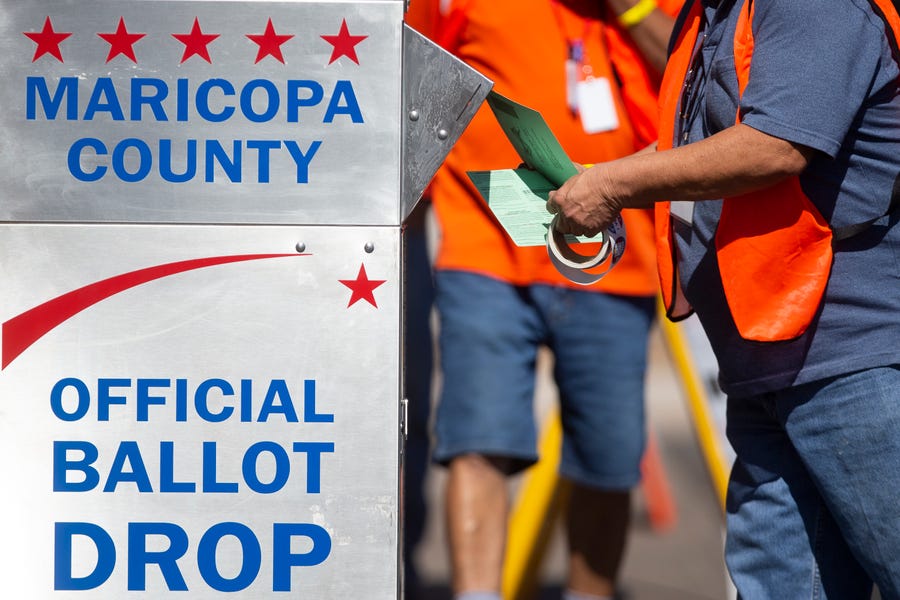

One Arizona member of Congress participated in protests outside Maricopa County’s election facilities even as ballots were being counted; three GOP members of Congress from Arizona later voted to set aside the state’s election results.

The circuslike atmosphere drew Trump die-hards, election conspiracy theorists and far-right media that simultaneously created buzz and fed off it.

It raised cash for Republicans and doubts for voters, threatening public confidence in elections here and elsewhere.

Interviews with dozens of people connected with the drama at the Arizona Legislature and the Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix, where the ballots were examined for months, make this much clear: The spectacle that unfolded here was a partisan obsession pushed by Trump’s close allies and made possible by just a handful of people in Arizona.

It didn’t have to happen this way.

Before Fann ordered the ballot review, for several days in December, Bowers, Fann and the Republican chair of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, Clint Hickman, tried to reach a deal for a joint audit conducted by an accredited firm.

Over four months, The Republic examined a trove of text messages, emails and court records, many made public after suing the state for access. Reporters spoke to decision-makers, consultants, staff, contractors, campaign aides and others tied to the review of the presidential and U.S. Senate races. Some talked on the record about their experiences, while others spoke on the condition they not be identified in order to speak candidly about private conversations.

The Republic uncovered efforts to circumvent the popular vote to engineer an illegitimate Trump victory. Once the results were certified, Trump and his allies shifted to a campaign to pressure local Republicans to overturn election results from voters who were using an early ballot system largely shaped over decades by their own party.

Trump, Giuliani, Fann and others who helped bring about the ballot review did not respond to repeated requests to discuss their recollections of the events leading to the review.

Bowers shared his story for the first time over three interviews totaling nearly six hours. The interviews took place by phone, in his office suite, and on the patio of a Cracker Barrel in the East Valley, where he verified key dates from his red leather-bound journal.

Like most of Arizona, the speaker watched the scenes unfold from the periphery as Fann steered the Senate into a probe led by the Florida-based Cyber Ninjas, a company with no prior experience in election reviews that is run by a man who publicly stated the election was tainted by fraud.

Fann has not yet explained her U-turn from favoring an accredited audit to authorizing a review led by partisans. Those who know her and did speak said she sought to quell Republican anger over Trump’s loss and could not resist the pressure campaign from his allies.

Early on, Bowers remembered offering her a stark assessment: Some of Trump’s most ardent supporters in the GOP-controlled Legislature viewed Trump’s election grievances as political opportunity.

“Karen, this is about trophies,” he said he told her. “This is about trophies on the wall — that individual members want to be able to say, ‘I forced them to do this.’”

Before the Veterans Memorial Coliseum became the proving ground for conservative conspiracies, it was the location of a rally at perhaps the high-water mark of Trump’s presidency.

The economy was in the final days of the longest expansion in U.S. history. Coronavirus seemed like a foreign problem in a faraway land. Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont who described himself as a democratic socialist, had won the New Hampshire primary the week before. Biden finished fifth.

Trump’s approval rating was inching upward after his acquittal in his first impeachment trial.

So it was on Feb. 19, 2020, when Trump strode onstage to a near-capacity crowd at the coliseum. Like most of his campaign events, it seemed to mix the noise of a rock concert, the passion of a religious revival and the sideshow elements of a carnival.

Two supporters carried Ervin Julian, a 100-year-old World War II veteran, down the coliseum’s steep stairs to a front-row seat on stage behind Trump and in front of the boisterous crowd.

One of the men carrying Julian wore a shirt that said “We are Q” on the front and “17 WWG1WGA” on the back. It is a phrase adopted by the QAnon conspiracy movement that stands for “Where We Go 1 We Go All.”

One by one, Ducey, all four of the state’s Republicans in Congress, Fann, Bowers and Kelli Ward, the state Republican Party chairwoman, took the stage as Trump praised the state’s GOP team.

“With your help, we are going to defeat the radical socialist Democrats,” Trump said early on. “We have the best economy, the most-prosperous country that we’ve ever had and the most powerful military anywhere in the world.”

Trump’s 82-minute, triumphal speech left his supporters delighted and his campaign confident that he was well positioned to again win a state he had narrowly carried in 2016, when he defeated Democrat Hillary Clinton by 91,234 votes.

Trump’s victory that year extended Arizona’s run of wins for Republicans in presidential races. The GOP won 16 of 17 presidential contests in the state beginning in 1952.

Trump’s electrifying optimism, shared by thousands of his supporters inside the coliseum, seemed rooted in political inevitability. In hindsight, Trump’s prospects began dimming almost immediately after that rally.

Less than a month after Trump’s speech, Biden took control of his party’s nomination, pitting Trump against the candidate best positioned to win Arizona and the one Trump worried about most. The coronavirus soon exploded into a pandemic that locked Americans inside their homes, upended the political agenda and brought a sudden end to a decade-long run of economic growth.

The state’s presidential preference election on March 17 and the rapidly worsening health crisis raised the first real concerns about voting and election management in Arizona, and they largely came from Democrats.

By then, COVID-19 was beginning to spark fear across the country, and the White House had called for a 15-day national quarantine to halt the virus. Democrats moved their final presidential debate to Washington, D.C., from Phoenix because of the widening crisis.

Sinema sent Hobbs a link to a Twitter post by a political website that said polling sites could be hazardous during a pandemic. At the time, little was known about the virus and its spread. Some feared shared items, such as pens, could help spread the coronavirus.

“File a request to the Az Supreme Court ASAP asking you (to) postpone,” Sinema texted. “This is what Ohio just … Did. You can file a special action right now.”

“Who is this,” Hobbs responded in a text.

“Kyrsten. I would file a special action NOW. We do not want to be the state that violated the 15 day effort to stop the virus. The governor has been very slow to move on every precaution. That is his choice, I guess. But you do not have to be like that. You can do what needs to be done. I am going to say the election should be postponed publicly very soon.”

Hobbs responded, “Understood.”

Maricopa County Recorder Adrian Fontes, a Democrat, wanted to mail ballots to every voter in the primary because of the coronavirus.

Neither change happened, but for Republicans, who didn’t have a primary election, both ideas raised concerns about voting.

The GOP-dominated Maricopa County Board of Supervisors had taken greater responsibility for management from Fontes in 2019, especially on Election Day operations and emergency issues. But the state’s far-right figures didn’t view board members as reliable allies if there was to be a battle over results.

Meanwhile, Trump had his own worries in Arizona.

In May 2020, the president held a meeting in the Roosevelt Room in the White House to discuss the state of play in Arizona.

Trump was worried that Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., was losing to challenger Mark Kelly and could “drag” him down as well, those familiar with the discussion said. The president wondered whether the GOP should run someone other than the incumbent against Kelly, the well-known retired astronaut. Then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., who had joined the discussion, made it clear he stood by McSally.

The GOP ticket had other worries, too.

On July 1, Vice President Mike Pence flew to Phoenix to assure the public that Arizona would have enough ventilators to manage the rising COVID-19 caseload.

Privately, Pence had other matters on his mind.

Away from the news cameras, inside a conference room in the Lincoln J. Ragsdale Executive Terminal at the Phoenix airport, Pence asked how the campaign was preparing for November.

“What is your plan for absentee early voting? Are you guys ready for any of the changes that would come of COVID?” Pence asked, according to someone familiar with the conversation.

People on hand told the vice president that 80% of Arizona’s electorate routinely vote by mail. It startled Pence, who was following up on concerns Trump had raised because other states, such as Georgia, Michigan and Pennsylvania, were expanding mail-based voting because of the pandemic.

Election officials in key 2020 swing states made significant changes to their election systems. For example, Nevada sent every registered voter a mail-in ballot for its summer primary. Several Pennsylvania counties, including those in the Democratic-heavy Philadelphia area, extended the postmark deadline for that state’s August primary.

Pence learned Arizona has signature verification and other security provisions in place.

Arizona Republicans assured Pence they were “comfortable” with the state’s early voting system and would “keep our eye on Adrian Fontes.”

Ducey expounded on voting in Arizona during an Aug. 5 public appearance at the White House, with Trump at his side, to discuss their management of the pandemic. Trump groused about mailing ballots to voters in Nevada. Ducey defended the widespread practice in his state.

When the cameras were gone, Trump seemed pleased with the governor’s answer. The president exuberantly asked Ducey if his state needed any additional help.

But the August primary created more anxiety for Republicans. Democratic turnout matched the GOP’s, and after Trump’s attacks on mail-in voting, many Republicans held onto their ballots until the last moment before dropping them off at the polls.

One GOP figure said the daily mailed-in returns of Republican early votes had “fallen off a cliff.” Trump’s team on the ground in Arizona was alarmed.

Trump always had another, unique problem in Arizona that would cost him: his feud with the late Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

McCain forged a bond with Arizona voters over his almost 36 years in office. He won all 11 House, Senate and presidential races he ran in the state. In 2016, McCain received more votes in Arizona than Trump did.

Trump’s broadsides against McCain, extending even after his death, didn’t matter to most Republican voters. But they did matter to some, and in a close race, it had an outsized impact.

Beginning in the early days of his presidential run in 2015 and continuing into the final months of the 2020 election, Trump attacked McCain in personal terms.

The attacks cost Trump support among women, moderate Republicans and independent voters who respected McCain and found the attacks unpresidential.

For more than a year ahead of the election, political pollsters and experts warned that Trump was in danger of losing Arizona, in part as support eroded among these key constituencies, especially in parts of Phoenix and its suburbs where the late senator had dominated his races.

Despite the warnings, Trump kept up the attacks.

At one point, Trump personally asked Ducey to help keep the senator’s widow, Cindy McCain, neutral in the race, people familiar with the request said.

A person close to Cindy McCain said the governor never asked her to withhold an endorsement in the race. A spokesman for the governor would not characterize Ducey’s conversations with McCain, saying they were private.

Though Trump’s campaign hoped “to keep her on the sidelines,” they sensed she was “moving in the wrong direction,” someone familiar with the strategy recalled. “And that’s going to be a problem for us.”

In September, The Atlantic magazine published a story citing unnamed sources that said Trump complained when flags were lowered in observance of McCain’s death in 2018.

“What the (expletive) are we doing that for? Guy was a (expletive) loser,” Trump said, according to The Atlantic.

The president denied The Atlantic’s story, although other media outlets substantiated some of the remarks attributed to Trump.

Trump responded with a tweet saying, “Never a fan of John. Cindy can have Sleepy Joe!”

Democrats followed her announcement with an ad blitz that put her words on screens across the country, especially in Arizona.

The Arizona Republican Party later censured Cindy McCain.

In a series of Saturday video conferences from their homes in the final weeks before the election, Ducey and his team advised top staffers in Trump’s campaign to maximize their visits to the battleground state with appearances outside of Phoenix.

Trump and Pence visited eight cities other than Phoenix in the final month in an effort to build a rural firewall.

Ducey’s team suggested Trump call into country radio shows and talk about how his policies affect their jobs, their pocketbooks and their families.

One person familiar with the calls said Trump’s political team knew “Arizona was going to be tough.”  Arizona counts its mailed-in ballots first, and fewer Republicans sent in early ballots in 2020, instead dropping them off at the polls.Thomas Hawthorne/The Republic

Arizona counts its mailed-in ballots first, and fewer Republicans sent in early ballots in 2020, instead dropping them off at the polls.Thomas Hawthorne/The Republic

While Trump, Pence and their surrogates zipped in and out of Arizona to try to shore up support, Biden and his running mate, Kamala Harris, barely visited.

The GOP campaign rallies left Republicans fired up about their prospects — and poorly prepared for an election loss.

Hours after the polls closed on Election Day, Fox News made an aggressive, but ultimately correct, call that Biden had won Arizona. Four hours later, The Associated Press followed suit.

Arizona was the first state projected to fall from Trump’s winning 2016 coalition, and it raised the specter of further losses in states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. All of those states, plus Georgia, eventually did flip to Biden, but it wasn’t immediately clear that would happen.

Trump responded to the quick Arizona call in an overnight news conference from the East Room of the White House that effectively gave license to his supporters to cast the election as stolen.

“This is a fraud on the American public,” Trump said at 2:30 a.m. Nov. 4 to a cheering crowd. “Frankly, we did win this election. … So our goal now is to ensure the integrity for the good of this nation.”

The president said he wanted “all voting to stop” and said his campaign would be headed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Instead, the Trump campaign leaned heavily on officials at Fox News, hoping to undo their Arizona projection. In the days after the quick call, Ducey’s 2018 deputy campaign manager walked conservative host Sean Hannity and two senior executives with Fox News through scenarios that indicated why the state remained within Trump’s reach. The Ducey aide gave a similar briefing to the Trump campaign.

While Trump could not fathom how periodic updates could shift the race so dramatically in Arizona, campaign insiders were long accustomed to close races and results that changed over days as ballots were counted.

Arizona counts its mailed-in ballots first, and fewer Republicans sent in early ballots in 2020, instead dropping them off at the polls. Those votes were tabulated last, after Election Day voters’ tallies.

In 2018, Sinema won her Senate seat after six days of counting. In 2016, U.S. Rep. Andy Biggs, R-Ariz., won his first primary election by 16 votes after a recount shifted only a few dozen votes over 17 days.

After the quick call for Biden in Arizona on Nov. 3, raucous protesters gathered outside the building where Maricopa County officials counted ballots.

By then, some Trump supporters suggested — falsely — that election officials provided them Sharpie pens that could bleed through their ballots and eliminate their votes. It was a conspiracy theory amplified in conservative circles, including by Eric Trump, the president’s son.

For people like Fontes and Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone, also a Democrat, it was not a moment to explain the intricacies of ballot markings; they feared violence.

Dozens of people — some clearly carrying firearms — swarmed the parking lot area outside the county’s election offices.

Mindful of the deadly clash in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, Penzone put several armed response teams inside the building and had dozens of other deputies in the area on standby “to protect the systems, the ballots, the people — everything in there.”

Fontes, the county recorder, called it a necessary response to a charged situation. At one point, the angry crowd pulled an election worker into their unprotected area.

“This person literally had to get physically wrestled away from a group of them and pulled back into the building,” Fontes remembered. “It was in my head that there would be casualties. It was in my head that we would have to be cleaning blood out of the warehouse because they were ready, they were armed. … They came to assault my staff.”

Protests went on for days, with U.S. Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz., fueling accusations of a stolen election. Alex Jones, a conspiracy monger who called the 2012 massacre of children at an elementary school in Connecticut a “giant hoax,” used a megaphone to exhort protesters to maintain their fight for Trump.

The Sheriff’s Office has spent an estimated $1.2 million on law enforcement efforts tied to the election and ballot review, including on demonstrations and protection efforts. The tab may not yet be final.

While Trump signaled the beginning of a drawn-out fight in the hours after the election, McSally, the Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, all but disappeared from public view.

McSally didn’t formally concede her race for days, but by Nov. 9, several of her key campaign staff were vacationing in Mexico. She wound up losing to Kelly by 78,806 votes.

When the presidential ballots were fully counted on Nov. 14, just 10,457 votes — fewer than the number of people who fit in the coliseum — separated Biden from Trump. The 0.3 percentage point difference made it the tightest presidential race in state history.

Unpredictable: A pandemic and the president’s anti-mail-in ballot rhetoric turned the conventional wisdom about Arizona votes upside-down

It was a bitter disappointment, but it wasn’t a complete loss for Republicans.

The GOP maintained its hold on the Statehouse, and Arizona’s four Republicans in Congress were reelected. Republicans accepted those results, made in the same election that delivered Trump’s loss.

But Republicans loyal to Trump could not accept his defeat.

Along with daily protests at the Capitol, thousands of emails, voicemails and text messages were left for Arizona officials in the days following the election.David Wallace/The RepubliTrump supporters across the country bombarded Arizona election officials and lawmakers with staggering numbers of emails, voicemails and text messages.

Like Trump, many voters could not reconcile the energy of his campaign with the quick call for Biden and the ever-tightening margins in Arizona. Democratic gains in traditionally red Maricopa County fueled suspicions that Trump’s loss owed more to cheating rather than his limited appeal.

State Rep. Shawnna Bolick, R-Phoenix, said she received 57,000 emails in the first two months after the election — and still gets some.

At one point early on, Bowers’ secretary told him the office received more than 20,000 emails and 10,000 voicemails each day. After receiving 9,000 text messages at one point, now-Sen. Paul Boyer, R-Glendale, got another phone number.

The messages often maintained fraud tainted the election, and Democrats and their allies were covering it up. Many were vulgar; some were threatening.

“It is criminal for state legislators to certify a fraudulent election,” one message to Bowers said.

“Rusty is going to prison,” another email said. “80,000,000 patriots will make sure of this.”

“Fix this mess of an election now, do NOT let the people who committed obvious fraud, intimidation, threaten & lie & who did Not win into our Whitehouse,” read another.

The din included more than just Trump supporters, lawmakers said.

“In all of my time in office, I’ve never seen the magnitude or type of people telling me their concerns about the election,” said state Sen. J.D. Mesnard, R-Chandler.

“Many of them have been from far-off places,” said House Majority Leader Ben Toma, R-Peoria. “It’s safe to say there’s been a ton of pressure to do something.”

One thing that set Arizona apart from other close states was the trajectory of the race.

In Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, Biden staged come-from-behind victories. Trump drew closer in Arizona’s initial count before falling short.

Trump and Giuliani zeroed in on people in Arizona who could still make a push.

It wouldn’t be Ducey, who had shown little interest in raising doubts about the election. And it wouldn’t be Hobbs, the Democratic secretary of state, who defended it on national television.

The president and his lawyer targeted Bowers and Fann, the Republican heads of the Legislature.

The weekend before Thanksgiving, a top White House aide called around, looking for cellphone numbers for both.

Those close to Fann said she felt squeezed by the most conservative members in her caucus. She was preparing for the holidays and didn’t want to discuss the election. She seemed to want to put off talking to the president and his surrogates.

When the White House came calling, Fann needed a strategy.

“What are we going to do? … They’re putting pressure on me — the national folks want to have fact-finding committees to find out about the fraud in Arizona,” Bowers remembered Fann saying. “She said, ‘They’re trying to get in touch with me and we’ve got to make sure we’re on the same page.’”Both Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers (top) and Arizona Senate President Karen Fann were in the Trump team crosshairs.Thomas Hawthorne/The Republic

They never had a chance. Right after he hung up the phone with Fann, Bowers received the call from Trump and Giuliani while sitting in his Prius.

By itself, the call was memorable for Bowers. It became amusingly so when he needed to search the small screen on his cellphone to find his lawyer’s contact information for the president.

A natural raconteur, Bowers joked to Trump and Giuliani he might have a story for his grandkids one day: that he accidentally hung up on the president.

“Trump just busted out laughing,” Bowers remembered. “He said, ‘That’s funny.’”

Then Bowers really did accidentally hang up.

The White House called him back, and Bowers and Giuliani shared a laugh.

Bowers needed some levity.

While Arizona’s election stirred national passions, Bowers, 69, was privately tending to his dying daughter. Her liver was failing, and she was rejected for an organ transplant.

Inside his house, and later in a hospital, Bowers saw his daughter’s life slipping away.

Bowers documented the eventful period, as he routinely does, in his handwritten journal through pages and pages of tight cursive writing. It is a distinctive practice for a man with many interests.

Bowers’ weathered face betrays his love of the outdoors, but perhaps his greatest passion is art. He paints and has sold sculptures. At least once, Bowers passed time in the often-mundane setting of the Legislature by building a miniature pinewood derby car for his grandson on his desk during breaks.

Bowers’ call with Trump and Giuliani revealed two of his more obvious traits: Bowers can be pleasant, but he’s no pushover.

“Rusty is a cowboy,” said one Capitol insider, in a reference to his independent nature.

Fann, 67, grew up in Prescott, one of Arizona’s most conservative areas. Decades ago, she started a transportation business that puts up guardrails to keep motorists safe.

She was elected to municipal government around the Prescott area where politicking didn’t overshadow problem-solving.

‘What’s happened to Karen?’ Election audit puts spotlight on Senate president after decades in office

She brought political pragmatism to a legislative seat at the Statehouse, where she has served for a decade, the past two terms as president of the Senate.

Fann, too, has a life outside politics. She likes to golf and cook. She is known to bring homemade pies to friends and is part of a dinner club.

Her agreeable nature often leaves her in the middle of the warring factions of her Republican caucus.

Her confidants at the Statehouse include lobbyists from both political camps who have worked with her for years. Her philosophy on the job is “‘We’re in this thing together, we’ve got to pick up the trash, we’ve got to do it, let’s work together, let’s figure things out,’” one Democratic lobbyist friend said.

If the ballot review sometimes felt like a political crucible, it also gave Fann a national political identity.

But at the Statehouse, she had one goal: retain her role as Senate president. Unlike Bowers, who won his leadership post despite the misgivings of his party’s far-right members, Fann owed her position to the more conservative members of her chamber.

Her friend, former state Sen. Steve Pierce, R-Prescott, a relative moderate, lost his title as Senate president after the 2012 elections to then-Sen. Andy Biggs and spent four lonely years out of power. Her friends say it was a loss Fann didn’t want to repeat.

Includes information from Arizona Republic reporter Mary Jo Pitzl.

Trump hates that Constitutional Oath, similar or the same as the one he took when he lied to become president of the United States. For months now, he has been doing everything possible to replace honest Republicans in Congress, state legislature, and in positions over state elections with loyalist MAGA liars and cheats.

And Trump is doing whatever it takes to get rid of honest Republicans that live by the oath they took, even murder if necessary hence all the death threats Republicans are getting who live by the oath they took.

“Donald Trump says the Jan. 6 mob chanting ‘hang Mike Pence’ was ‘common sense’

Opinion: It should be noted that a guy who wants to be president again tacitly endorses expressions of violence against a vice president carrying out his constitutional duties.”

https://www.azcentral.com/story/opinion/op-ed/ej-montini/2021/11/16/trump-mob-chanting-hang-mike-pence-not-common-sense/6402075001/

“When They Fantasize About Killing You, Believe Them”

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/08/when-they-say-they-want-kill-you-believe-them/619724/

Likewise, red states are continuing to use extreme methods of gerrymandering in order to sway elections in ways that ensure minority power. New laws in 19 states make it harder for people, particularly people of color, to vote. Democrats need to do more than sing Kumbaya. They need to pass the new voting rights legislation ASAP before the midterms.

Thanks for that Atlantic link, Lloyd. I think…?

Disgusting. Immediate action must be taken! Trump and his henchmen must be punished! Quick, establish a committee to think about this for the next 20 years!

Oh, and Mr. Garland, how’s the golf game coming along? Hope you are enjoying your retirement!