Ray Salazar, a teacher in Chicago, wrote a blog post asking me to respond to four questions. I will try to do that here. I am not sure I will accurately characterize his questions, so be sure to read his post before you read my responses.

Before I start, let me say that he obviously hasn’t read my book Reign of Error. Consequently, he relies on a five-minute interview on the Jon Stewart show and a 30-minute interview on NPR’s Morning Edition to characterize my views. Surely, he knows that sound bites–which is what you hear on radio and television–are not a full representation of one’s life work or message. I am very disappointed that he did not read my book, because if he had, he would have been able to answer the questions he posed to me, and he might have asked different questions, or at least been better informed about my views and the evidence for them.

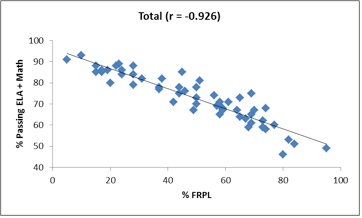

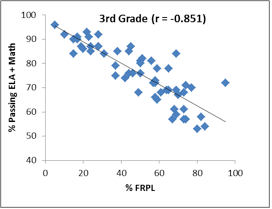

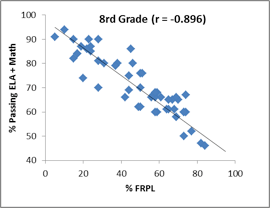

First, he objects to my statement that poverty is the most important predictor of poor academic performance, even though it is empirically accurate. He claims I am making excuses for poor teaching and that I am saying that we can’t fix schools until we eliminate poverty. But in my book, I make clear that we must both reduce poverty and improve schools, not choose one over the other. He says that teachers can’t reduce poverty, can’t reduce class size, can’t control who takes arts classes, and have no control over external circumstances. This is true, but he doesn’t seem to recognize that my book was not written as a teachers’ guide, but as a guide to national and state policy. Policymakers do control class size; do control resources; do make decisions that either lift children and families out of poverty, or shrug and say “let the schools do it.” There is no nation in the world where school reform has ended poverty, nor will school reform end it here. Salazar does not seem to understand that I am trying to open the minds of Congressmen, Senators, Cabinet officials, Governors, and State Legislatures, that I want them to take action to improve the lives of children and families; I want them to understand that they should not be cutting the jobs of librarians and nurses and increasing class sizes, and they should not be tying teachers’ compensation to test scores. I agree with Salazar that teachers make a huge difference in the lives of children, but I want him to acknowledge that the deck is stacked against poor children. It is stacked by circumstances, and it is stacked by our schools’ obsessive reliance on standardized tests. Standardized tests are normed on a bell curve. Bell curves do not produce equality of educational opportunity. They favor the advantaged over the disadvantaged. We as a society have an obligation to do something about it. He would understand all this far better if he read my book instead of listening to a TV show and a radio program.

His second point accuses me of opposing standards because I do not support the Common Core standards. That is ridiculous. I support standards, but I don’t support the federal imposition of standards that were written mostly by non-educators, that were adopted because of a federal inducement of billions of dollars, that have never been tested anywhere, and that–as the tests aligned to them are rolled out–cause the scores of students with the highest needs to collapse. In New York, for example, 3% of English learners passed the Common Core tests, along with 5% of students with disabilities, and less than 20% of African American and Hispanic students. The two major testing consortia funded by the U.S. Department of Education selected NAEP proficient as the cut score (passing mark) for their tests; that is an unwarranted decision, because NAEP proficient was never intended to be a passing mark for state tests. It represents “solid academic achievement,” not “passing.” Only in one state–Massachusettts–have as many as 50% of students reached the 50% mark on NAEP proficient. Thus, the testing consortia will either be compelled to drop the cut score (and claim progress and victory) or more than 50% of students in the U.S. (and far more in urban districts like Chicago) will never earn a high school diploma. Of course, I want to see students in Chicago and every other urban district reach high levels of performance, but that won’t happen until politicians stop cutting the school budget, stop laying off teachers, ensure that every school has the resources it needs for the students it enrolls, stop using test scores for high-stakes for students, teachers and schools, and make sure that all children have food security, access to medical care, and the basic necessities of life. Salazar seems to suggest that poverty doesn’t matter all that much, as long as teachers are creating a “college-going” culture. In effect, he is shifting blame to teachers for failing to create such a culture; but no school can create such a culture without the tools and resources and staff to do it.

Third, Salazar criticizes my concern that school choice is intended to create a marketplace of charters, leading to a dual school system. He wants more school choice. I don’t think school choice answers the fundamental challenge to school leaders: how can they create good public schools in every neighborhood? That is their duty and their obligation. Salazar says that good neighborhood schools don’t exist now, and I agree. But choice won’t bring the change we need. It will create a competition for a few good placements, but it wont create more good schools. Choice does not improve neighborhood schools. it abandons them. We will never have good neighborhood schools if we create a system where all kids are on school buses in search of a better school. In some cities, it is the schools that do the choosing, not the students or their families. Many of those “schools of choice” don’t want the kids who will pull down their all-important scores. So, what should happen right now? The mayors of big cities who want to be education leaders should make sure that every school has the resources it needs: the teachers, librarians, social workers, nurses, after-school programs, summer programs, small classes, arts classes, physical education, foreign languages, etc. In a choice system, it is left to students to find a school that will accept them and hope it is better than the one in their neighborhood. I say that students, parents, educators, and communities must demand that the politicians invest in improving every school. As Pasi Sahlberg, the great Finnish expert, has said about his nation’s schools, “we aimed for equity, and we got excellence.” As for Ray’s crack about my “choices,” I attended neighborhood schools: Montrose Elementary School; Sutton Elementary School; Albert Sidney Johnston Jr. High School; and San Jacinto High School. Were they the best schools in Houston? I have no idea. They were good neighborhood schools.

In his fourth point, Salazar repeats his belief that there is both a poverty crisis and an educational crisis. I agree. If he read my book, he would know that. The poverty crisis created the educational crisis. If we ignore the poverty crisis, we will never solve the educational crisis.