The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities in D.C. issues reports on high-profile issues. This one should be in the hands of every legislator, school board member, and policymaker. It succinctly explains why states should not authorize vouchers.

Iris Hinh and Whitney Tucker wrote this report, which was published in June 2023. One conclusion is clear: vouchers inflict damage on public schools, attended by the vast majority of children, while helping affluent families. .

Hinh and Tucker write:

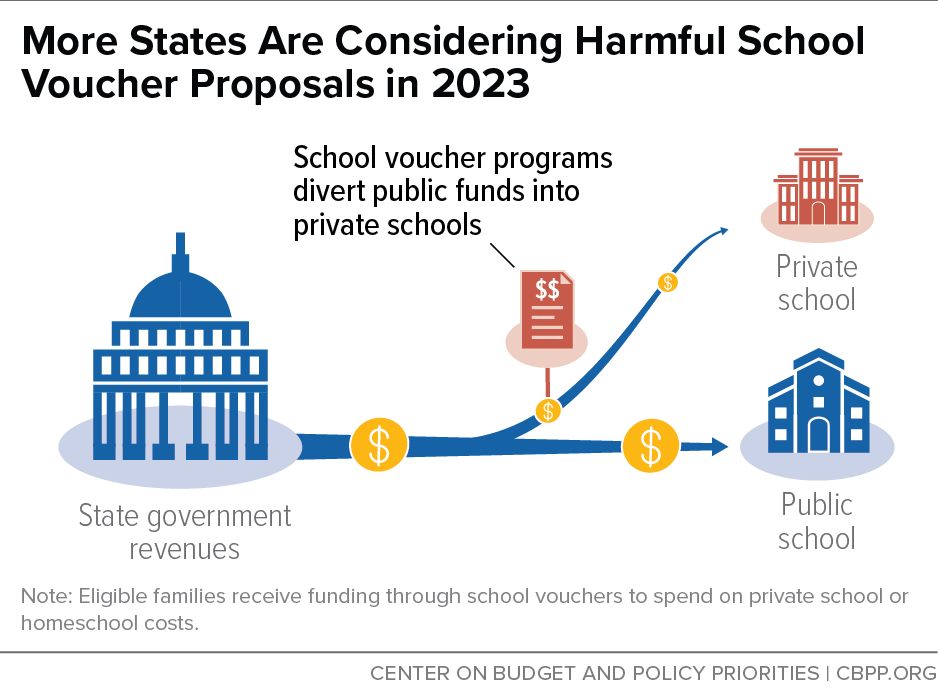

K-12 school vouchers are typically funded through state revenues and give families a set amount of money per eligible student to cover a portion of private school tuition. These vouchers divert money away from public schools, sometimes by directly re-routing education funding to private schools, and other times indirectly by making it harder to pay teachers, buy new textbooks, and provide quality after-school programming. The support for public schools is high: families overwhelmingly support their schools, and many teachers and other advocates for public education oppose vouchers.[1]

In the past few months, state lawmakers have expanded and created a record number of school voucher programs with little to no limits on eligibility. This will deplete available state revenues for public education and other critical services and do little to expand opportunity for students.

Regardless of whether school vouchers directly or indirectly divert funding from public schools to private education, state K-12 funding formulas depend on some metric of student count to allocate per-pupil funding. Some school districts can absorb some of the cuts with layoffs and reduced spending on textbooks and supplies. But fixed expenses such as air conditioning, school buses, and building maintenance can lead to funding shortfalls and layoffs.

In early 2023, these states created or expanded their school voucher policies:

- Nebraska passed the state’s first voucher program, a K-12 tuition tax credit initially capped at $25 million annually, though the cap could rise to $100 million a year depending on demand for tax credits. Individuals and businesses can donate up to half of their taxes owed (with a maximum of $100,000); donations are funneled to scholarship granting organizations (SGOs), which pay private school tuition and other eligible expenses on behalf of students and their families. The tax credits reduce tax liability and thus, decrease the state revenues available for investments in public services, including public schools. Public school advocates are planning to challenge the bill on the 2024 ballot.

- Arkansas’ LEARNS Act created, among other harmful policies for public education and teachers, an education savings account (ESA) program, which will phase in universal eligibility by the 2025-2026 school year and provide state-funded vouchers for families to use toward private school tuition and several other allowable expenses (like homeschooling, exam fees, and tutoring).

- Florida broadened eligibility requirements to make its existing ESA program available to all students (rather than only students with disabilities or those from low-income families), with an estimated cost of $4 billion in the first year of implementation.

- Iowa created an ESA that is initially targeted to families with lower incomes. But it will expand over time to include all students by the 2025-2026 school year and cost over $340 million per year when fully in effect.

- South Carolina expanded the state ESA, lifting household income eligibility to 400 percent of the federal poverty level beginning in 2026-2027, but placing a 15,000-student cap on the program.

- Utah created an ESA starting in the 2024-2025 school year that is available to all students but gives priority to students based on their household’s income.

Other states should not follow the paths of these states. For one, school vouchers primarily benefit wealthier students, families, and businesses. States with existing voucher programs — Arizona, Missouri, New Hampshire, and Wisconsin — have reported that most families who benefitted were already covering the costs of private schools and homeschooling prior to the voucher becoming available.

Wealthy people and companies also benefit when vouchers take the newer form of K-12 tuition tax credits. People and companies who donate to SGOs are allowed to opt out of paying tax to fund public needs and instead fund tuition scholarships at private K-12 schools. This tax incentive can provide state credits — up to 100 percent of the donation — to families with incomes over $200,000 and even allows businesses to profit from claiming federal expense deductions and avoiding capital gains tax.

Vouchers can also increase the likelihood that students experience discrimination and harm. Private schools are not required to offer the same federal civil rights protections for students as public schools. In fact, many voucher bills explicitly require families to waive students’ protections and rights under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act for educational services that students with disabilities may need to learn.

Further, vouchers do not necessarily expand opportunities for students with the greatest needs. Students from families with low incomes often face barriers to navigating the voucher application and private school admission processes. Smaller, rural areas often rely on their local public schools as community hubs and primary sources of employment. Private schools can more easily push students out without recourse based on how they style their hair, what they wear, test scores, and subjective disciplinary action.

Voucher costs often grow beyond what is projected and thus, reduce overall revenues for other state spending. A recent study of school voucher programsin seven states shows how state voucher spending from 2008 to 2019 increased by hundreds of millions of dollars annually, while K-12 spending for public education declined despite public school enrollment increases. Arizona became the first state to implement a universal voucher program in 2022, and as of mid-March 2023, the ESA program is expected to cost the state at least $345 million more than initial projections for the first year. New Hampshire’s voucher program was estimated to cost $130,000 in 2021 and it now costs $14.7 million. And a few private schools in Iowa are already raising tuition only a few months after the new voucher program passed in January of this year.

Some state lawmakers understood the great cost at the expense of public services and stopped multiple school voucher bills this year. For example, 16 House Republicans broke with their party to defeat Georgia’s universal voucher proposal in the final hours of session. And Idaho Senate Republicans raised concerns about the long-term cost of a universal ESA bill, which also applied to subsequent voucher bills.

As some states continue to debate school vouchers during legislative sessions, state lawmakers should understand that their actions now and in the future will have large fiscal and harmful consequences for public education and student opportunities.

Another state that did NOT pass vouchers was Texas, even though Governor Greg Abbott called four special sessions of the legislature. Rural Republicans refused both bribes and threats and voted against vouchers because they wanted to protect their community schools.

The graph above appeared in an earlier version of this report, published in March 2023.

Universal vouchers are a way for the affluent to get the public to subsidize their children’s tuition or their corporate taxes. These vouchers are schemes to socialize the expenses of those that have money, and both these schemes drain public school budgets and deplete their resources. In both schemes the result harms the education of most students, and they will likely result in higher taxes for working families. The well-to-do and corporations benefit, while working families and public schools are the losers in this transfer of wealth ploy.

LikeLike

I am astounded that the people in this blog do not want vouchers. I f we give every kid $50,000, every kid will get an education like every other kid. Think about it. Every kid will be in a small class like an elite private school. Every teacher will be paid like they taught in an elite private school. Every school will have enough money to do whatever it wants.

To fund this, so we can be fair, I propose a 25% flat tax on all purchased items, so the poor will be sure to still pay for the rich.

LikeLike

To fund this I propose a 70 percent tax on incomes above 2 million a year.

LikeLike

Universal vouchers are like socialism for the affluent. It’s like saying that I want a new Mercedes, but I only have $50,000. I want to use tax money to pay for the rest because I deserve a fancy new car. As a result everyone will have to chip in to pay for my personal choice. This pass-along schemes are from the people that scream and yell about socialism. It’s more hypocrisy from the right wing.

LikeLike

And news out West states…

https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/science-of-reading-reforms-show-student-gains-in-california-study-finds/2023/12?utm_source=nl&utm_medium=eml&utm_campaign=eu&M=8451130&UUID=c7503a1de5c7cb9342b7f33da6cca4ff&T=11211400

This piqued my interest especially since my son teaches fourth grade in Wisconsin and the entire state has adopted Science of Reading. But, if they money runs out, the researchers say, “We don’t know how it will sustain itself.”

LikeLike

“Reforms rooted in the “science of reading” improved student test scores by the equivalent of a quarter of a year of learning, a new study from California shows—providing some of the first evidence that recent policy efforts to bring early reading teaching in line with research have led to gains in student achievement.”

Did I just walk into a 2,000 hog CAFO?

Or maybe a 50,000 head of cattle feed operation?

Because there is a lot of manure in that sentence.

What is the agreed upon by all reading experts definition of a year of learning?

LikeLike

It is easy to boost test scores of young students with an emphasis on phonics. For a district with lots of poor students, it is much harder to make big gains in scores when reading shifts from learning to read to reading to learn in middle school. Comprehension is a far more complex skill that requires a lot of prior knowledge, experiences and language that most poor students may not have as a foundation. These scores are often referred to as the “middle school slump.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

The story about the new study in CA supporting “science of reading” includes this claim:

“In examining the results of California public school data, the researchers concluded that, over a two-year period, the science-of-reading methods resulted in achievement gains equivalent to one quarter of a school year — compared with similar schools that were not using the approach.”

I wrote to the reporter for clarification. The kids gained 1/4 of a year in two years?

LikeLike

From the new study:

“At one participating Los Angles Unified school, Principal Ramon Collins said reading attainment at the Young Empowered Scholars Academy in South L.A. was simply unacceptable, despite a hard-working, dedicated staff. In the year prior to the pandemic, in English language arts, 77% of the school’s students tested as far below proficient — the lowest category. In 2022, when testing resumed, that number worsened to 85%. But last year, that number dropped to 64% — a vast improvement, even with much work yet ahead. “

2/3 of the kids still fell behind….

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-12-04/stanford-study-wades-into-reading-wars-with-strong-evidence-that-phonics-works

Most principals in LA say they have been teaching phonics since 1999.

LikeLike

@Diane, a couple of the things that hit me were the Science of Reading was based in phonemic awareness — wow, never thought of that. And it was based on K-3. Correct me if I am wrong, no matter how much emphasis is put in K-3, most kids level out about third grade and the real proof is how well students take what they learned and apply it in the later grades. When I interviewed nearly all of my students, they said they started hating school and hating reading after third grade. And the “1/4 gain in two years.” After teaching nearly all grade levels, I had seen all the programs that were the panacea come and go, “Read 180”. “High Point” yet the one program (can’t remember the name, but it was very comprehensive for reading and writing) – axed within one year. The last year I taught we used Study Sync (a canned program) that the kids hated (Study Stink) which made them hate to read even more. The Accelerated Literacy program tested them repeatedly until they didn’t care. I never saw anything that just said, “Hey kids, we are going to read for the love of reading. And guess what? When you get stuck, I will be there to help you. Sound fun? Now, let’s go on a reading adventure.” I also saw the famous phrase (paraphrased), “…it was cheaper than teaching reading correctly, so, yeah…this will do for now…until the money runs out.” Drove me nuts.

LikeLike

These so-called studies and half-assed reporters simply take on faith the notion that the reading tests validly test for reading ability. They do not. From that false premise, false conclusions result.

LikeLike

It is totally bizarre that across the entire landscape of K12 education research, these half-assed tests are taken extraordinarily seriously despite their fatal flaws. That they are is a deep indictment of the entire education research industry in the United States. What a bunch of charlatans.

LikeLike